THE ART OF CARLOS LUNA

The art of Carlos Luna is UNIQUE. For many reasons. He was born in the year ’69—erotic number—of the 20th century, in San Luis, Pinar del Rio, Cuba. There he began his education, which he continued and completed in the island’s capital during the profligate and tumultuous decade of the 80s. Without doubt, the 80s served as the larger school for Luna and for many who studied art at that time. Those years impacted decisively, in one way or another, on every aspect of Cuban culture and every sector of the country.

With regard to the visual arts, the 80s were a period of intense debate and aesthetic-ideological confrontation, possibly the most fecund and far-reaching in the history of Cuban plastic arts.

A polemical discussion was initiated as to whether or not “getting up to date” by adopting the languages of Postmodernism was inevitable. The party ended like the feast of Guatao[1]: with an open and massive questioning—above all on the part of the youngest artists—of the sociopolitical reality of the country, which was then breaking the mold of “within the Revolution everything, outside the Revolution nothing”, dictum imposed by Fidel Castro in 1961.

The intransigence and stagnancy—at times violent—of the Revolution, incapable of learning the obvious historical lesson of the debacle of the Socialist camp and the disintegration of the Soviet Union, provoked the exodus of numerous artists of different generations (and of tens of thousands of Cubans). It is thus that Carlos Luna settled in Mexico and tenaciously developed an opus that would very soon reach maturity.

Luna’s work leaves little room for indifference: it radiates a shocking magnetism that soon becomes captivating. Contemplation is always a second phase when viewing it. The first is amazement. It is well worth allowing oneself to be seduced and to enter into the powerful body of images which, rather than calling our attention to them, assault us. It is not difficult either. He is nothing like the all too common “artists’ who attempt to hide their vacuity by appealing to conceptual elaborations—their own or those of others—which are also ultimately empty. Luna’s work is complex but intelligible, at times scandalously direct. It is profound, because it comes from deep within, and fecund, because it goes deep in. It has been explored and interpreted well by intelligent, respected professionals, and deservedly valued—and acquired—by important collectors. Yet its intrinsic richness always stimulates new points of view.

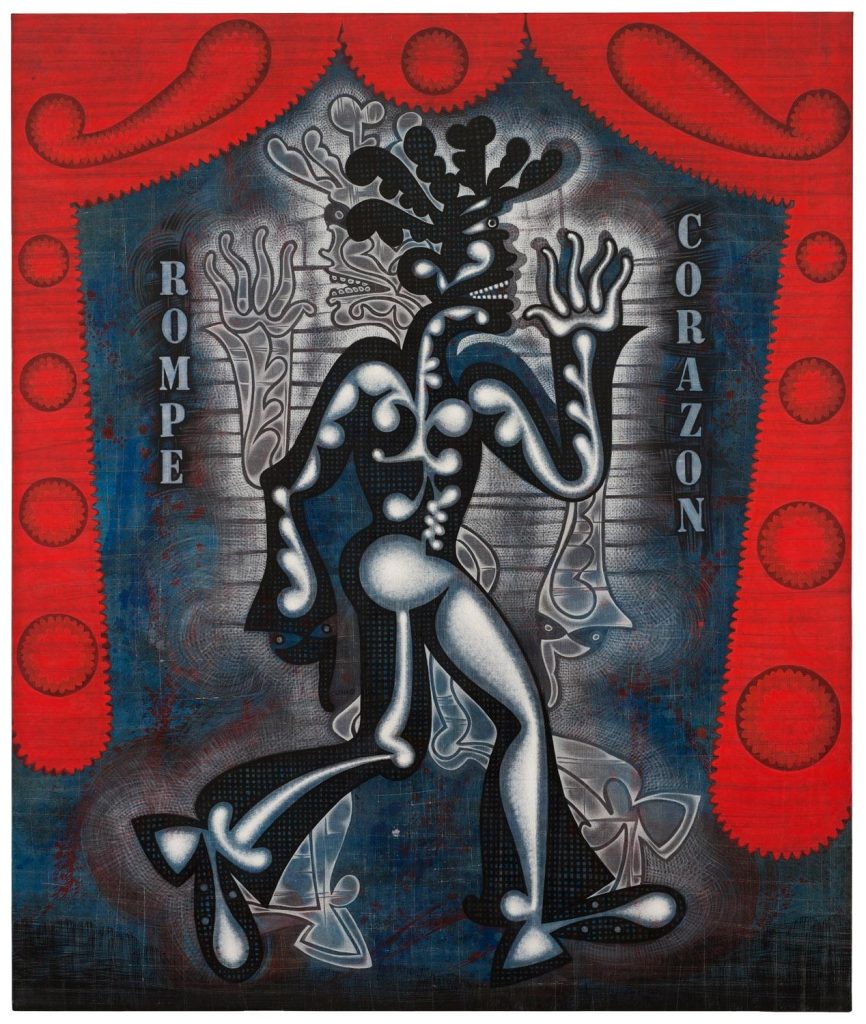

Creator of sculptures, drawings, ceramics and objects, Carlos Luna is essentially a PAINTER. Painting is the heart, the solar center from which all else emanates. And his paintings are territories populated, or overpopulated, by figurative and abstract subjects of diverse histories, which exude the life of the artist—and of Cuba—and bear witness to his passionate and uninhibited spirituality. Roosters, horses, bulls, cows, crocodiles, doves, scorpions, airplanes—many airplanes—knives, firearms, flowers, forms—decorative or not—trees, words, gods, eyes—many eyes—Fidel Castro (frequently decapitated), a cocky peasant, and the WOMAN, always the same woman (a clear symbol of Claudia, his wife and mother of his children.) One must add to this the interpenetration, the hybrid identity of many of these pictorial subjects: the peasant turns into a rooster; the rooster into a bull; a tree is also a vagina; the vegetation is phallic or animist with eyes instead of leaves; a head springs out of a word; the peasant ejaculates a stream of flowers; the airplanes resemble cigars or penises seeking some place to stick themselves into. Except for the WOMAN. The woman is always the same: beautiful, voluptuous, fertile, meticulously adorned and very dignified: a noble figure even when the peasant abducts her. It is true that eroticism inundates Luna’s canvases and it manifests in a direct and challenging way. The woman is coveted. In order to get her, the gods are called upon, but she is never denigrated. Luna’s painting always expresses feelings of uncontainable virility, eroticism, and LOVE—but not machismo.

The PEASANT is, of course, a multiple self-portrait of the painter himself. Also a plural portrait—real or imaginary—of many people, women or men, of the countryside (or not), Cubans (or not), who are or would like to be like him, open and fearless. He wears a hat, a shirt, a moustache from the 19th century proclaiming that he is from before, of now and forever. But he doesn’t wear farmer’s boots, only Sunday walking shoes. The pictures allude to periods of his life, affirming his passions and opinions—political and existential. It doesn’t matter to him who’s watching; they have the easy-going manner with which the people discuss things out in the street. It is worth adding that many of the figurative or abstract protagonists, from the visual plot transmitted or reiterated from picture to picture, conduct themselves in the same way.

The frequent appearance in his paintings of the image of curtains, together with his particular alteration of forms and abrupt movement of the leading figures, has been associated with the theater, specifically puppet theater. Apart from external similarities, the characters that live in Luna’s paintings don’t hang from any thread like marionettes, and if they interpret any narrative it is that of themselves and of their particular magical surroundings. The theatrical is a metaphor for the very LIFE in which Nature, humans and their gods struggle immersed in a turbulent, burgeoning stream of events. These events can be of any type, even violent, although it should be noted that in that case, Luna’s vision also exudes a joking tone that recalls the Cuban choteo[2] but transcends it. If in fact the “choteo”, in its most primary and negative form, turns everything into a joke, it also covers pain by making fun of things, and tends to avoid—through decompressing—the overwhelming gravity of what affects us, Luna is the opposite. He faces and challenges adversity. He counterattacks with mordacity, lucidity and precise aim. On the other hand, in his work there also abound things that are taken very seriously and evoke the artist’s unequivocal commitment. Luna attacks but he also respects, even reveres: his homeland, his wife, his children, his freedom, his people, LIFE. Jorge Mañach in his renowned Indagación del Choteo [An Inquiry Into The Choteo] affirms that “the time has come to be critically joyful, rigorously audacious, and consciously irreverent”[3] This is precisely Carlos Luna.

How does the painter succeed in communicating to us what his painting says and at times scream? Luna’s capacity for formal invention is EXTRAORDINARY. One believes it only because one sees it. The expressive distortion of natural forms is constant—changing (reinventing) its configurations, its sizes, its positions, its structures, tonalities and colors. This he effectively combines—or fuses—with abstract forms. No less important is the use of purely decorative forms, with such daring that they surpass the condition of mere adornment to become signs of unsettling value. If we add to this the calibrated but resonant intervention of words and sentences written forward and backward within the picture, we have completed an initial summary of the visual means the artist utilizes to express himself.

His ways of representing are surprisingly imaginative. Nothing manifests as we would perceive it outside of his paintings and yet in them everything renews its essence: we identify each thing, but in a fresh, new way. The rupture brings the viewer closer rather than distancing him. It generates empathy, not rejection. In “A Quemar Penas Compay” [Burn Sorrows, Compay] (1998) his alter ego—the rooster—appears, resolutely placed on the head of a deity. His body is simplified, summarized and, at the same time, exaggerated through forms that are volumetric, voluptuous, rotund, which synthesize feather, muscle and determination. The rooster is gray, austere, metallic, but incombustible. In the background, a precise and dynamic structure of geometric forms of different shades of red burns free and effective like fire. Even further back, the newly gray forms are no longer committed to any particular denotation: they are purely abstract vectors, which are joined to the whole and add vigor to it. An omnipresent black line runs throughout the composition. It serves as a skeleton, outline and energy transmitter. In “Untitled” (1998) the geometrization is more extreme, as it is in “La Pose y el Encaje” [Pose and Lace] 1998), “Circo y Maroma” [Circus and Somersault] (2006) and many others. In these works, extremely rigid, straight-line forms define the exterior of the central figures and contain, but don’t enclose, systems of curved forms that integrate the figures within. These interiors are resolved with large tubular forms, which define one or several parts of the body, or with independent fragments that float on the plane but connect visually. A rhythmic succession of brief brush strokes delineates them with painstaking certainty. This exterior/interior dichotomy is it only clothing/body or does it also connote appearance/essence? In other works, a wider form envelopes certain figures like a protective aura that likewise expands and emphasizes their movement. In others, that aura is woven in textures through fine, clear brushstrokes, like a glow.

One work that stands out for its provocative effect is “Untitled” (2001). Executed in black and white on a rustic coppery background of amate paper, the swear word CABRÓN [Bully] occupies almost the entire visual field. The rooster-peasant, calm on top of a stool, makes an admonishing gesture with his hand of a man to the fellow whose head is springing out of the belly of the C., brazenly smoking (the tobacco smoke forms the shape of a phallus). The two languages, images and letters, are fully integrated in this insult of great physical and moral dimensions. In order to produce such an image the painter must have guts. Unlike the well-known—and monotonous—use of text by conceptual artists, which so often renounce pictorial values, here these values reclaim the linguistic sign. The letters are just as much painting as the rest. They are possessed by the magic and grace of the brush that endows them with spikes or dresses them in white balls as though made of cotton. Does this denounce the duplicity of the bully, capable of looking handsome although it may be evil? On the upper edge peeks out a curtain. This indicates a scene suggested, but not encompassed, by the image. At the lower edge, on the left, we see four sharp ovals like leaves of a cactus entering the picture. To the right, shadows that projected the aggressive word toward the spectator. We are standing in front of the arena in which the cabrón is accused so that the whole world may know. And whom the shoe fits may wear it.

The space is never passive; there is no rest in Luna’s paintings. In the works done on amate paper, the very texture—tactile and visual—of the medium brings a rough complexity to the backgrounds merely accentuated by their natural earth and bark colors. Nonetheless, on occasions this is not enough for Luna and he superimposes a grid of black lines traced at freehand drawing. Why? He knows why; this is how he feels it. Other types of paper and the immaculate canvas soon lose their virginity with layers of paint that are then scraped, flayed, as if to discover entrails, which the brush stroke was incapable of revealing. Once the work is finished, the successive layers of pigment are unable to hide the traces of those merciless movements of the spatula or the knife, which mark the picture with the scars of their elaboration and reinforce its privileged condition of a handmade product. Every space in the work, including the most humble and apparently secondary, is imbued with that vibrant density. It is on such a surface that the artistic materials organized by the drawing gradually begin to grow, layer by layer. Ink, charcoal, pencil, gouache, oil with intermediate layers of varnish as the case may be. Gouaches intentionally torn when half dry, brushstrokes through which tones and shades ascend and descend, or which fill wide planes with quick and uniform dots of paste, as if assembling space and color grain by grain with the mystical patience of a goldsmith. This is the depth of the painting. But its length and width are difficult to estimate because the expansive force of the forms frequently tends to go visually beyond the physical limits of the format. Many of his paintings seem to be fragments of a greater composition, how big no one knows. Nonetheless, they are organized with such skill that although they could go on indefinitely in all directions, they hook the viewer in and capture his attention, making him focus on what is before him, which is the vortex of all those possibilities. This is particularly evident in a work of the magnitude of “El gran mambo” (2006), without doubt one of his most important pieces.

Color is another of the crucial dimensions in Luna’s art. The word that best defines how he uses it is MASTERY. It must be said. In many paintings the spectrum of the misnamed “neutral” colors seems to be enough for him, going from white to black passing through an infinity of grays. A notable example “Waiting for” (2013). In other paintings he uses a full range of colors with virtuoso sensibility: “Adrian’s Colt” (1993): “The Apostle Decides to Immigrate (1996); “Star Horoscope” (2010). His ability to limit the palette and get the most out of it in terms of radical contrasts deserves special emphasis, as in the previously mentioned “El Gran Mambo” and other works of the same period. Other outstanding examples in this sense are “Illuminated” (2011); “Dialogue” (2012); “The Annunciation” (2010); “Mr. C .O. Jones” (2012).

One of the fertile paradoxes of Carlos Luna’s art is that, while it is meticulously labored with an unusual technical rigor, the result is nevertheless as striking as if it were spontaneous. How is it possible that such a daring elaboration does not affect the freshness of his works? Part of the answer is that only mastery of the trade leads to excellence, to grace. The opposite is when occasionally the donkey plays the flute (which, unfortunately, is not uncommon and there is no lack of those who encourage it). The other part of the answer is that Luna takes pleasure in painting. What from outside appears arduous from inside is pleasurable. It is enjoyed with the same unrelenting care with which a lover wins over the body and soul of his partner. The famous Aragón Orchestra was already singing it in the ‘50’s: “Softly, softly, softly, that’s how one feels the most pleasure” [Suavecito, suavecito, suavecito es como se goza más]. He paints in the same way in which he satisfies his wife and sired his children. The sensuality, the eroticism of his art, isn’t circumscribed to a boldly explicit theme. It is something more basic, more inherent, which nourishes and irrigates the same process of creation from the time an idea takes over in his head until his hands give it final material form. Each of Carlos Luna’s pieces is a powerful focal point of vitality that enriches everything it shines on.

Carlos Luna’s talent is EXCEPTIONAL. His personality is solid as a pyramid. Among his many qualities stand out fearlessness, the capacity to learn from the world, and, no less important, to listen to himself. He genuinely belongs to the élite of artists who possess and fulfill the four cardinal points of creation: head, hands, heart and balls. This permitted him to assimilate and synthesize, in an organic, natural manner both intuitive and cultivated, everything that suited him from the broad repertoire of European and American art of the 20th century, and also from Mexican art—especially popular art—and the diverse legacy of Cuban Modernism. He is heir to and faithful transmitter of the heroic impulse of that Exposition of New Art celebrated in Havana in 1927, sponsored by the Revista de Avance, which, through a mysterious dialectic of environment and memory, has been impregnated and transfigured in the work of numerous artists of the island. But he is the only one of his generation in Cuba who chose that path independently, going against the current, in conditions of extreme difficulty. And he has honored it with the highest professional quality and a message that is multifaceted and exciting for the mind and the senses.

The art of Carlos Luna is original, authentic, irreducible to the sources that served him as a reference during its formation. It has a unique, unmistakable stamp which reveals an authentic communion between the refined and the grotesque, the complex and the direct, the intimate and the political, between the vernacular, taken on with pride, and in-depth inquiries about the human condition.

My wish is that all factors, both from this world and the other one, come together even more in his favor so that he can continue to create freely.

©Alberto Jorge Carol

[1] Expression in the Cuban oral tradition indicating that an event degenerates into a brawl (T.N.)

[2] Cuban colloquial term for a kind of crude sarcasm that has the intention of diminishing the status, seriousness or dignity of a person, discourse or belief. (T.N.)

[3] Mañach, Jorge. Indagación del Choteo. Miami, Florida: Mnemosyne Publishing [1940] 1969, p. 80. Mañach’s text was first published in Revista de Avance, Havana, Cuba [1928].

Back to WRITINGS

Back to WRITINGS