PABLO PICASSO CERAMICS | CARLOS LUNA PAINTINGS A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH

It is sometimes difficult to reconstruct the birth of an idea. Showing the paintings of contemporary artist Carlos Luna (b. Cuba, 1969) alongside the ceramics of Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) is one of those times. Executive Director Irvin Lippman and I were relatively new to the Museum of Art | Fort Lauderdale and in the process of assessing the permanent collection. We were eager to see and show the Picasso ceramics so generously donated by Bernie Bercuson, a collector from Miami Beach. At about the same time we were introduced separately to Carlos Luna and, entranced by his work, decided to invite him to be Artist in Residence for 2008-09 and to participate in an exhibition that would present both his own work and the Picasso ceramics. Luna accepted the challenge.

What is most striking about the work of both Picasso and Luna is its incredible vitality, even potency. Both artists’ work has often been discussed in those terms. Their most successful paintings, whether done on canvas or paper or in clay, exert an incredible magnetism on the viewer. Their work seems to cast a spell on you, to hold you captive and transport you to a higher state of consciousness and aliveness.

The question of what magic animates their work is difficult to answer, especially when one feels like a trespasser in territory that is best left unexplored. But there are a few things that can be considered. Both artists seem to understand the necessity of plumbing the depths of the creative process by drawing on personal experiences, by engaging with the art that was not, nor is, consciously created as Art with a capital “A” – Egyptian art, religious art (both Western and tribal), outsider art, caricature, and graffiti, to mention just a few possibilities – and by engaging with the actual craft, the process of drawing, painting, and forming.

Picasso was voracious at absorbing artistic influences. Perhaps because he had such a facility for drawing, he was constantly pushing the rules governing classically influenced representation, especially of the human form. His most significant innovation came in 1907 with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, a painting that began as a warning about the dangers of contracting syphilis in a brothel, and ended, by ushering in the Cubist revolution, as the premier icon of modernism. Inspired by African tribal sculpture, the story goes, Picasso changed the heads of two of the five female nudes – whose fractured bodies were already based on Iberian and Assyrian sculptures – into masklike faces, giving the painting a rawness that shocked even his artist contemporaries. Realizing that African sculptures were magic objects, intercessors, mediators, fetishes, even weapons, Picasso called Les Demoiselles his first exorcism painting, implying that it was the first painting in which he exorcised the accumulated legacy of the Western (that is, European) art tradition.[1]

As if in celebration of the liberation of Paris at the end of World War II, and perhaps to break the isolation the war had imposed on him, Picasso had an intense encounter with lithography, a medium he had previously used only occasionally. His subjects were two female heads, a pair of nudes, and a bull. Since bulls and bullfights had been prominent in Picasso’s art since childhood, it seems logical that the bull was the most resonant choice. What Picasso wanted to hold onto was the metamorphosis of a painting during the process of creation. But since that was impossible, except through photography, he turned to lithography, where different states of the work could be pulled intermittently from the same stone and could record his process of creation-through-destruction. The bull began as a brute physical presence and arrived, 11 states later, in the form of a quintessential cipher.[2] There can be no question that for the artist this exercise, too, was a kind of exorcism, or cleansing, most likely of the brutalities of the war. Part of his inspiration must have also come from the fact that he was drawing a subject on stone that has been around since man’s early beginnings.

A year later, in 1946, Picasso followed that intense experience of drawing on stone with his rediscovery of clay in Vallauris, in the South of France. He was familiar with the medium from Spain and from his encounter with the ceramics of Paul Gauguin upon his arrival in Paris in 1900-1901, followed by a few other incidental experiences.[3] But in the summer of 1947, he returned to Vallauris, a place that had been associated with pottery since Roman times, and began seriously working in ceramics at the Madoura Pottery, creating over the next 25 years thousands of one-of-a-kind works and works in editions. He was clearly looking for a more hands-on experience to fuel his creative imagination, but according to his dealer, he was also looking for a more permanent and stable support for his painting than canvas provided.[4] Inspired by his recent experience with lithography, he was excited as well by the possibility of creating ceramic multiples that would enable him to share his vision with a wider audience. This populist sentiment went along not only with his politics but also with the deep connection he felt to the artisans he worked with at the factory. He identified with their sense of purpose and the satisfaction they derived from their craft.

Picasso lived for his art, and his art lived because of him. The power he was able to translate into his ceramics, even into the works in editions, came from the fact that it was based on life, on personal experience. It appears that Picasso collected all kinds of animals. Part of his menagerie included an owl whose behavior he must have closely observed. Only through such an intimate connection can one transform a production vase into a belligerent wood owl (91.32.9), or depict the very essence of “owlness” with a few deft lines on a pitcher (91.32.23). Doves and other birds, as well as fish, also figured prominently in his ceramics over the years. In 1950 Picasso’s household included a goat, Esmeralda, who was part pet, part model for a life-size bronze sculpture. Esmeralda was also immortalized in a series of ceramic portraits. With her head silhouetted against the black background of the plate, one can almost hear her chew the green grass protruding from her muzzle (91.32.70).

Picasso attended bullfights since he was a child and made drawings of the corrida at least since he was 11 years old. Moving to the South of France reconnected him with the ancient ritual, and it became one of the first subjects to occupy him when he turned to ceramics. He was able to transform ready-made platters into arenas – complete with audience and blinding sunlight – in which to stage this spectacle of life and death (91.32.16). There are also plates that show bulls in more bucolic settings, but in contrast to these, the Tauromachy scene in black on red ground, harking back to ancient Greek black figure painting, shows a triumphant bull standing over his victim in all his majesty (91.32.39).

Picasso’s deepest and most constant source of creative inspiration has come from the women he knew intimately and loved. Picasso equated sex with painting. All the ceramics in the Museum’s collection that feature women date from 1954 onward, from the time when Picasso was just beginning his last great relationship with Jacqueline Roque, a woman he met at the Madoura Pottery. Three pieces unmistakably bear her image; the most striking of these is a pitcher that shows her almond-shaped eyes and aquiline nose. The regularity of her features gives the work a sense of tranquility and timelessness that complement the timelessness of the medium. The other two pieces are plaques, one of which shows Jacqueline’s classic profile drawn with ivory slip on a brown background. The second, an impression taken from a linocut, transforms Jacqueline’s face through the otherworldly stare of the eyes into an image of spiritual power that resounds with the Catalan Romanesque, so influential on Picasso’s road to Les Demoiselles (91.32.27, 37, 56).

From early in his career, Picasso has recorded his own face with the same honesty Rembrandt displayed in his self-portraits. Although they are not technically self-portraits, one can speculate that most of the plates, tiles, and plaques that feature male heads are a form of self-portraiture. Beginning with the depiction of the Flute Player of 1951, which associates the artist with the Greek nature god Pan, one can study the artist’s changing moods as he struggles with aging. In Face with Goatee (1968-69), he seems to be poking fun at himself as an old goat, while he appears to be a little kinder in Man’s Head of the same year. But the most amazing of this series is simply called Face (1960), a portrait in relief of white clay that seems to reach back in time and reminds us of our origins (91.32.7, 62, 47).

What can be said about Picasso’s ceramics in editions is that they are true works of art through which the artist communicates to us his worldview and life spirit. It is to the credit of the collector that he was sensitive to these simple yet telling objects that came late in the artist’s life but represent artistic renewal at a time when he was also rejuvenating his personal life by fathering two children. Although Picasso did not shy away from the subject of death and destruction – his painting Guernica attests to that – or from man’s everyday struggles, he preferred to make life-affirming work that to this day communicates his energy.

“Reading” Carlos Luna’s paintings presents more of a challenge than understanding Picasso’s ceramics, which are distilled essences. Painting as a medium is more complex, and Luna’s paintings, being of the moment, still have not been quite assimilated; they are in a sense terra incognito. But several analogies can be drawn between Picasso’s and Luna’s work. Probably the most obvious is the artists’ relationship to women. Women in all their various aspects play a central role in both artists’ work. Woman as the keeper of the hearth is represented by Luna in the iconic painting of his grandmother Juliana in Café caliente, or Hot Coffee, Juliana (2004). Judging from the body language, there is no question of who is in charge in this tableau vivant, which is as hieratic and timeless as an Egyptian tomb painting. The sewing machine that looks like an Egyptian offering table comes into its own in a recently completed painting dedicated to the artist’s mother. In My Mother’s Lean Years (2008) the artist situates the sewing machine in the middle of an abstract composition. With the title/subject of the painting clearly spelled out, Luna seems to be honoring this inanimate object by making it come very much alive, as if it were an active participant in his mother’s survival. The reading of the scene as a sacred communication is reinforced by the placement of Elegguá, the messenger of all the Afro-Cuban orishas, underneath the table.

Romantic relations between the sexes are as salient a topic for Luna as they were for Picasso. The sentiments range from flirtation, to courtship, to abduction, to more or less explicit references to sexual encounters, to the power struggle of Latin lovers brandishing weapons. The quasi-serious, quasi-humorous encounter of the couple in Latin Lovers (2008) can no doubt do much to put the battle of the sexes in perspective. Luna has surrounded the pair with an abundance of observant eyes, flowers, and water in the presence of the ubiquitous Elegguá, as if to conjure a more peaceful resolution to their conflict.

There is no doubt that sex is a creative force for Luna as it was for Picasso, both in an overt way and in the form of abstract energy. The passions he unleashed on canvas and paper in the second half of the 1990s in Mexico are still palpable. While the female protagonist, affectionately called the “sexy lady,” is eternally young and beautiful, the male protagonist takes on many personae in addition to the basic Cuban country fellow, the guarjiro, Luna’s closest alter ego. In keeping with the artist’s country roots, his other personae are the rooster (in its two personifications, the rooster man and the masked rooster man), the horse, the bull, and the alligator. All are symbols of power that come to life under Luna’s brush the same way Picasso enlivened his animals, through firsthand experience. This is probably truest when it comes to the depiction of the roosters Luna raised to fight. In Bum Bah Tah (2006), in the secrecy of the night jungle, the guarjiro and the rooster man square off with their respective birds. One may say cockfighting is to Luna what bullfighting was to Picasso, a ritual reenactment of an ancient practice. One may also speculate that Luna had a more cynical subject in mind – that he was creating a metaphor for the Communist regime’s practice of setting one person against the other.

Luna, like Picasso, does not shy away from politics, and his cast of male characters gets involved. His political fantasies are focused on removing Fidel Castro from the scene by cutting off his head in That Uncontrollable Desire (2007); by blasting it off with a pistol in From the Hero I Series (2003); or by just finally having Death come to get him in Time is Up, You Bastard (2003). In the last painting, Death is headed for a curtain, as if the whole scene playing out is a magic trick. However, the many faces of Elegguá that frame the picture make it more an invocation or a prayer to higher powers.

Luna’s work has always had a mystical, spiritual side, but since moving to Miami roughly half a dozen years ago, this aspect of his work seems to have come into the foreground. In 1995, Luna painted an unusual work called El monte, which loosely translates as The Jungle. Set against strings of writhing female figures that sometimes seem to mutate into male sex organs, it features the floating head of a crowing rooster. The title also recalls the most famous painting of Cuban painter Wifredo Lam, which may have been Luna’s inspiration. Lam’s work dates from 1943, when the artist had returned to Cuba from Paris and was trying to integrate Surrealism and Cubist structure with Afro-Cuban spiritual concerns. The word monte or manigua is used to describe an untilled area of land that is considered sacred space in the traditional rural life of Afro-Cubans.[5] In Luna’s Bruca manigua or Wild Jungle from 2004, the guajiro sits sideways near the left side of the painting on a little red stool that in turn sits atop a large Elegguá (a small Elegguá is attached to the bottom of the chair). His body is set against a dark shadow, on which, at knee height, sits the shadow of a black bird. Although there is a field of undulating plants in front of him, the guajiro’s head is turned to the viewer, bearing a somewhat ambiguous mien. The vegetation is alive with all manner of objects that seem to morph into one another: gourds, eyes, mouths, horseshoes, knives, and, at the top, as if to hide what is below, fleshy-looking flowers. It is quite clear that we are contemplating a sacred grove filled with objects of magical power.

In the painting Muerto en vida or Like Dead (2004), the situation appears to be more extreme. The manigua, rife with symbolic objects, seems to have taken over completely. At the bottom of the picture, the severed head of a guajiro screams in anguish. Whether it is his heart that is being run through with a sword is not clear, but his situation is dire – that much is clear.

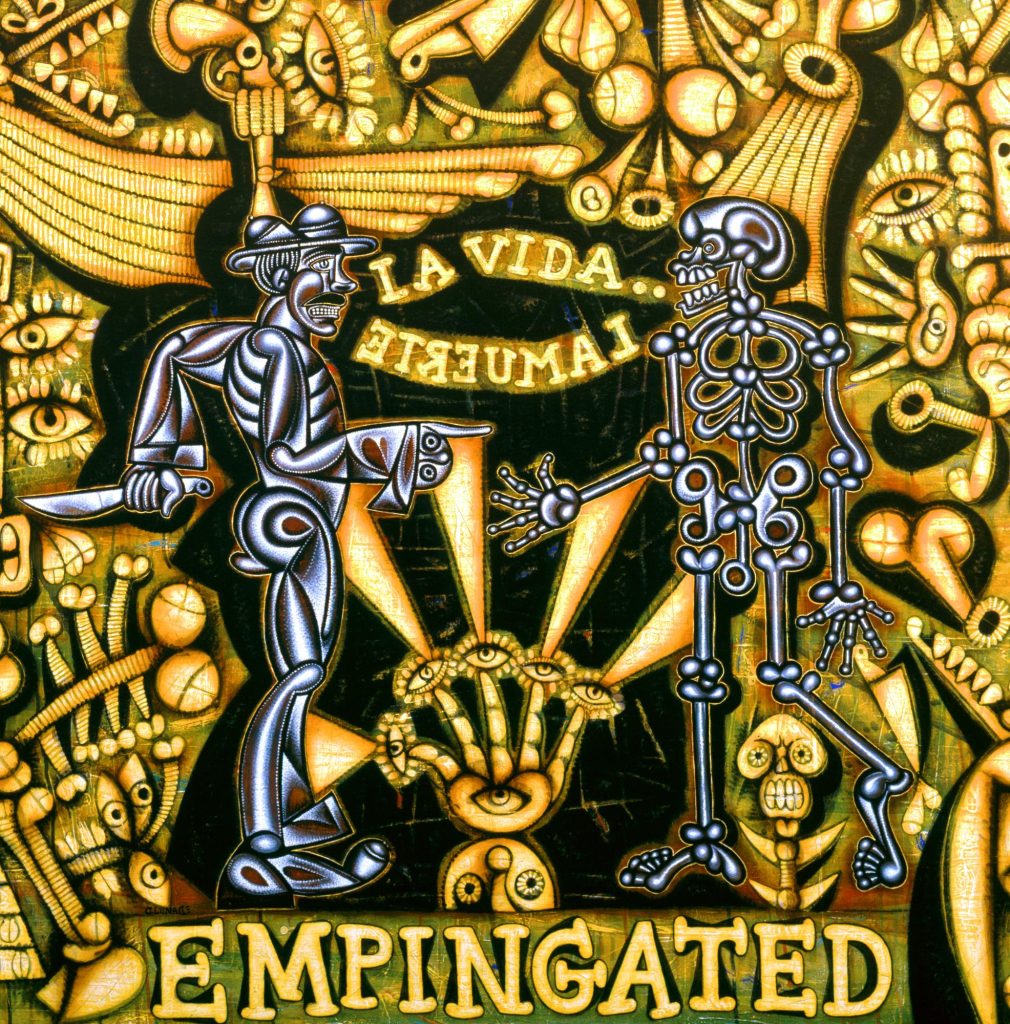

Perhaps painting The Grand Mambo (2006), the mural-sized summa of Luna’s life and work, has caused Luna to push the magical part of his work still further. Clearly two recently completed works, La cosa negra, , It’s a Black Thing and Empingated, are the most powerful Luna has yet created. It is the kind of work with which he is either calling on the spirits for help, or exorcizing them, the way Picasso wanted to exorcize academic influences from his work. The latter work, especially, seems to portray a life-and-death struggle that makes the painting feel like it would be more at home in a church than over the couch.

º º º º º º º º

At the time we invited Carlos Luna to select the Picasso ceramics to be exhibited alongside his paintings, he related a story that has since been published as part of an interview with critic Jesús Rosado. [6] When Luna was about 5 or 6, his first encounter with visual expression came from observing drawings in pencil and crayon that his father executed directly on his bedroom wall at a time of mental crisis. Although Luna never saw his father actually drawing on the wall, he was able, when his mother was not looking, to contemplate the drawings, which covered a plaster wall that measured about 2½ by 3 feet. Periodically, the drawings would be painted over to make way for another session. This powerful experience has clearly been a formative one for Luna’s art.[7] The most obvious thing one notices when looking at Luna’s painting is its hieratic, formal quality. It is that sense that probably inspired Irvin Lippman to call Luna’s work heraldic. The figures, their arrangement, and their relationship to one another have the quality of a frieze. They find their ancestors in a cross between Egyptian tomb paintings and street murals, the timeless and the time-bound, the sacred and the temporal, the secret and the public.

While Picasso found the perfect form by making endless drawings until the image on the paper conformed to the power of the image in his mind, Luna seems to arrive at a composition, then transfer it to canvas, changing it very little. It is what comes after that initial laying down of the image that is most important. Luna achieves his power not only through his subject matter, like the bull, but in the way it is painted. The process has been described as labor-intensive, but it is an act of communion with, and invocation of, higher powers. It is an invitation for the spirits to inhabit his paintings and make them magical.

Notes

[1] Irving Lavin, Past-Present: Essays on Historicism in Art from Donatello to Picasso (Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press, 1993), 245.

2 Ibíd., 222-243.

3 Titus M. Eliens, Pablo Picasso, Keramiek/Ceramics (Zwolle: Uitgeverij Waanders; ‘s-Hertogenbosch: Stedelijk Museum, 2006), 14ff.

4 Ibíd., 27.

5 Arturo Lindsay, Santería Aesthetics in Contemporary Latin American Art (Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1996), nota 16, 167.

6 Jesus Rosado, “The Bird of Paradise and Its Shadow: A Conversation with Carlos Luna”, en Carlos Luna: El Gran Mambo (Long Beach, CA: Museum of Latin American Art, 2008), 67.

7 El padre de Picasso, un artista académico de menor rango, también influyó en la formación artística de su hijo, pero de forma opuesta. Picasso creció pintando en el estilo realista académico de su padre, y por tanto luego pasaría el resto de su vida tratando de regresar al estilo directo e inocente –naïve- típico del arte infantil. Lavin, nota 55, 309-10.

A Word of Thanks and Recognition

Three distinguished authors contributed their insights to this catalog. We would like to thank them for their thoughtful essays. Two focus primarily on Carlos Luna’s work, while the third deals with the intersection of the art of both Carlos Luna and Pablo Picasso. Curtis L. Carter gives us a sweeping overview or summa of the artist’s art and life. He places Luna in the context of his culturally diverse but politically troubled Cuban homeland; in his adopted home of Mexico, where he established a family and flourishing career in his wife’s hometown of Puebla; and finally, for the last six years, in Miami, establishing his second home away from Cuba in the midst of the largest Cuban diaspora and contemporary art hot spot. Carter also relates the artist’s approach to painting to the philosophy of the American pragmatist John Dewey and the concepts of the Marvelous of Cuban essayist and novelist Alejo Carpentier.

If Carter takes a broad view in his essay fleshed out with discerning details, Carol Damian takes the opposite approach, using one central symbol and branching out from there. “The Tree of Life: Real and Fantastic” focuses mainly on the tree in Luna’s art, which she sees as the universal symbol that bridges the distances from Cuba to Mexico to Miami, accumulating as it does different religious and cultural associations and significations. Using the tree motif as her foundation, she touches on two characters -the guajiro and the rooster- that animate Luna’s work and are intimately connected to nature as symbolized by the tree. Following that line of thought, Luna’s fecund vision of the tree also becomes a means for the inclusion of the far-reaching narratives and stylistic sources in his work.

Jesús Rosado, in his thought-provoking essay “Picasso – Luna: The Center, the Fringes…and Vice Versa,” postulates (rightly) the demise of the formerly held notion of the difference between the artistic center and the periphery – here ostensibly represented by the protagonists of this exhibition, Pablo Picasso and Carlos Luna – that by implication long colored our perception and reception of works of art. Much has changed, however, since the time Picasso was at the forefront of modernist innovation in the early part of the 20th century, and now, in the first decade of the 21st century, the era of post-postmodernism. As Rosado points out, the “migratory displacements caused by the great political tidal waves,” of which Luna’s life is exemplary, along with advances in communication technology, have breached the boundaries of the center/periphery paradigm, making the Picasso/Luna exhibition an exciting proposition. Rosado sees the task at hand to find commonalities in the artistic language of the two artists in form, but even more to articulate a “concert of asynchronies, consonances, and common ground.” In that context Rosado discusses a number of sources the two artists share, but also reminds us that Luna was more influenced by the strategies Picasso employed to transform art historical antecedents into his own vision than the actual products of those transformations.

Back to WRITINGS

Back to WRITINGS