A PERPETUAL MACHINE: THE ART OF CARLOS LUNA

History resides in a popular stanza,

in a tired horse, in a ruined house,

in the plains, the plants, the leaves,

in a hero, in a martyr.

One must learn history.[1]

Manuel Moreno Fraginals

If we want to draw an outline of “Afro Cuban” art, we must start by placing its production within the main cultural issues that determine it and the artistic criteria that characterize it. We must also stress the historical presence of the numerous African ethnicities that wove Cuba’s intercultural fabric, with groups arriving from Spain and Asia. It is also important to discuss how those cultures and ethnicities interacted within the Cuban context –expressing a shifting sense of nationality driven by mestizaje–, by analyzing the historical factors that shaped them.

Among the ontological features that characterize Cuban culture one must consider its multiplicity, something that it shares with other Caribbean cultures. This quality becomes essential when one strives to place Cuban and Caribbean cultures within the wider context of Western history and culture. It is also important to consider that those cultures have played a strategic role in the regional cultural continuum.[2] Those forces have been remarkably active within the Caribbean, and have given voice to a regional discourse that takes exception to the inclusive and globalizing one put forward by Western culture.

This text begins by focusing on the definition of what has historically been construed as “aesthetic” within Western art and culture, and on how this concept has been applied in understanding Cuban culture and history. Cuban esthetic expressions have been approached and discussed with the objective of defining them according to their historical circumstances, using aesthetic parameters associated with a new sense of belonging defined across territorial/national lines. This has been undertaken in opposition to identifying and classifying Cuban artistic production in its relations with the metropolitan centers of cultural power (Spain or the United States of America, in this case), or under the limited gaze of theoretical methodologies applied to discussing Western art.

Also discussed are some esthetic and cultural ideas about Cuban and Caribbean art, including a historiographical draft of some of the artistic and critical frameworks that attest to a process of change in the theory and practice of art in the case of Carlos Luna. The idea is not to sketch a history of the artist’s esthetics, or of those of Cuban and Caribbean art in general, even though esthetics is certainly one of the tools that contribute to understanding Luna’s production in its cultural and historical dimensions.

Another important subject covered by this narrative is related to the historical implications of multiculturalism in the evolution of Cuban culture, and to the importance of this phenomenon within the conceptual framework of Carlos Luna’s works. A chronological sequence throws light on some principles that might help us explain those works in a dialectical sense, by comparing Cuban history with those of the Caribbean and Latin America, and by alluding to a national identity as opposed to referring to more specific formative elements that contributed to creating a multicultural local identity. Those references allude, for example, to esthetic subjects associated with African, Asian or European cultures. Linearity makes a lot more sense in art history manuals, where a chronological approach to artists and movements is more to the point. It seems to me that a critical sequence based on certain problematic issues is better suited to understanding the evolution of Carlos’ art and its relation with certain subjects relating to oral literature, popular culture, African religions and art in general.

Historically speaking, the search for a local awareness, and the subsequent inception of a national consciousness, first started in Cuba during the second half of the 18th-century. It is a process that remains active today. As a matter of example, we may find a budding feeling of distancing from Spain starting from the development of a local oligarchy based in Havana,[3] involved in military and maritime activities. According to Manuel Moreno Fraginals, “such oligarchy inherited and reworked their norms for social coexistence and their set of hierarchical relations from metropolitan Spain, and proceeded to adapt them to their colonial conditions, a new society and a different geographical environment. [4] We may identify this narrowly nationalistic first stage in the opposition between criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the colonies) and peninsulares (those who were born in and came from Spain).

Such is the case of the works by José Martín Félix de Arrate y Acosta, which Moreno Fraginals defines as the first attempt at self-recognition by Havana’s oligarchy. Such a notion of criollo is mainly defined by outlining a new kind of citizen with a history and a political discourse stemming from a different political space. We might be able to place this discourse of identity within the basic notion of “fatherland” [5] in its narrowest sense, associated to Havana’s physical and sociopolitical space. According to Moreno Fraginals, this limited idea of “fatherland” “leads, in the works of Arrate, to an insistence on certain features of the area known as Havana, related to weather, geographical situation and vegetation[6]. Besides, such discourse of identity required an expressive form to gain currency within the social classes that were struggling to claim a space and legal recognition within the network of relationships between the colonies and the metropolis. With this in mind, Arrate adopted a literary style that idealized and praised nature’s attributes in Cuba (Havana), as opposed to the discriminatory and segregationist discourse of the dominant classes, based on the physical and biological differences of those born in the colonies, which considered them “beings full of physical and moral imperfections” just for having been born outside Spain.

This might be one of the essential points in Arrate’s work, since it stresses a notion of “authenticity”, related to a definition of citizenship as outlined by the gaze of the cliques of metropolitan power, as opposed to a criolla consciousness of an “aristocratic, colonialist, slavery-inclined and racist” [7] nature. Conveniently, the latter notion extends the definition of the “Cuban nation” to the whole island, including people living on the fringes of society, such as Indians and blacks. I would like to point out that an important factor for the economic consolidation of the Cuban oligarchy was the establishment of the Real Compañía de Comercio de la Habana, in 1740. A second important event took place in 1789, during the reign of Charles V, when Havana’s aristocracy, associated with the metropolitan ruling classes, was granted permission to enter the slave trade. In this fashion, criollo merchants were boosted and a primary local capital for economic transactions within the isle was consolidated.

It is also worth pointing out that this period saw the consolidation of a social sector that imposed its physical and economic presence, besides demanding a political space within the city. This process started in 1600 with the foundation of the Compañías de Pardos Libres de La Habana. Later, around 1691[8], came the creation of the Cabildos de Nación, followed by the Cuadrillas en el Puerto Habanero, authorized by the Count of Ricla in 1763[9].

Another important development during the colonial years was that the city’s basic economy –driven by craftsmen, tobacconists, shoemakers, mechanics, tailors, barbers, masons, dentists, midwifes, and all those whose work was related to the arts (painters and musicians, to mention a couple of examples)– came to be dominated by the white population as of the foundation of Havana’s Academia de San Alejandro in 1818.

There were some political movements carried out by this sector, which was marginalized from power. Among them, we must point out countless rebellions, starting with José Antonio Aponte’s conspiracy, in 1812, followed by the uprising of the Lucumis, organized by Hermenegildo Jáuregui in 1835.[10] In this regard, I would like to call attention to the double-edged character of the institutions and societies formed by Havana’s marginalized blacks and mulattoes. On the one hand, those institutions acted as a mechanism of control and division of those sectors, but on the other they allowed a basic accumulation of capital within them, a process that was subsequently affected by the creation of political movements such as the Conspiración de la Escalera in 1844. Another very significant development was the doubling of the black and mulatto population during the 18th-century. For example, by 1774 free blacks and mulattos numbered around 90,000 people. And the Ten-Year War, which began in 1868, more than two decades after the so-called Conspiración de la Escalera, is now considered to be the first phase of the War for Independence, with an outspoken nationalistic, independentista and (conveniently) abolitionist character. This enabled the movement to involve most of the social sectors previously mentioned.

From these events, we can trace the beginnings of a nationalistic and foundational discourse, related to “belonging to Cuba” instead of Spain. It sprung from the different social classes coexisting on the island, and is the product of economic motivations, but also of a psychological attachment to a new social, topographic and historical context. This can be exemplified through several visible signs appearing on literary and visual-art productions, as well as on the legal system.

The new legal framework got consolidated by the formation of several political, economic and cultural institutions, promoted by Cuban intellectuals, aristocrats and the local bourgeoisie, in contrast with a discourse fostering cultural integration with Spain, considered as the Nation or the “Mother country”. This process went on well into the 20th-century during the First Republic, and is still alive today. This is attested by some concepts that have dominated Cuban cultural analysis, such as transculturation, syncretic culture, cultural hybridity and postmodernity.

Since this is a very complex matter, related to the continuing redefinition of Cuban cultural identity, a critical analysis of these concepts deserves an independent text. In the development of this work’s subject, I have only outlined their beginnings as a process.

Afro-Cuban culture was primarily characterized by providing a new value framework and a critical evaluation of the cultural and historical features that define and redefine it within the wider scope of Cuban culture. In principle, Afro-Cuban esthetics was defined by considering the idea of beauty or “the beautiful” as a functional or pragmatic archetype, closely related to certain cosmogonic, mythological and metaphysical visions, as opposed to a concept of beauty related to the idea of perfection or pleasure. Its ritual character leads to a functionality that optimizes it as an objectuality, beyond ending up as a fetish or object of seduction. In their origin, its esthetic manifestations are objects of power.

In this sense, professor Robert Farris Thompson defines art in African cultures, and in their equivalents in the Americas –Afro-transatlantic cultures–, as “that which jointly offers spirit and images, or ki-mooyo. This literally means, the language of the soul.”[11] Thompson bases his definition of art on the word ki-mooyo, establishing a link between the cultural experiences of Bantu peoples of central Africa and certain cultural forms originating in Congo that are prevalent in the Americas (Afro-Atlantic), in music, visual arts and religion. Thompson goes on to point out that “The concept of ki-mooyo opens our eyes to a hidden dimension in the reinstallation of African objects in the Americas”, [12] concluding the following on the concept of art’s transitional character in both continents: “The African visual presence in the Americas is constantly linked to the spirits, preparing us for a widening of our everyday horizon. Spirits do not need data. Spirits do not need visas”.[13]

Following Farris Thompson, the idea of beauty in African and Afro-Atlantic art springs from recognizing that there are objects, environmental experiences, corporal actions, dancing performances and rituals that express ideas about existence, spirituality and the “I” communicating with nature, the cosmos and ancestral forces. Beyond the concept of beauty, experiencing it is associated with a feeling that makes it part of a collective pursuit. This means that the unity among members of society is the consequence of a series of communication strategies articulating alternative manifestations of knowledge existing in graphic systems of writing, known as “firmas” (signatures), and also in oral literature and in ritual practices related to religion. In general terms, we might venture that “the beautiful” is a category comprising all that provides us with the necessary functional knowledge to grasping a philosophy based on certain principles useful for understanding nature and fate. It is thus that Afro-American groups see beauty where rituals exist, and the knowledge involved derives from human’s interacting with nature through certain “artistic” forms, ceremonies and religious experiences, plus other expressions of everyday wisdom and living.

AFRO-CUBAN ART AND ITS PROBLEMATICS

Striving to characterize contemporary Afro-Cuban esthetics, I have chosen some examples that illustrate the fundamental problematics in Afro-Cuban art, considering sociocultural factors, such as the “intercultural” condition of Cuban culture, the role of Cuban art practices in shaping a national cultural profile (or even a regional identity), and the way in which Cuban art expresses itself regarding certain issues that affect global art.

If we want to explore the expressive factors and conceptual elements inhabiting African cultural components in Cuban visual arts (and in those being produced in the Caribbean isles in general), it is imperative that we grasp certain artistic problematics. These problematics also help us to critically reflect on the role that African cultures have played within the Cuban artistic language.

According to our own criteria, those problematics are:

1. The nation as writing

It essentially refers to the traditional forms of representation in visual-arts language, such as painting, drawing, sculpting, engraving and photography. This problematics is characterized by the predominance of an esthetic discourse that evokes African traditions in a homogenous manner, viewed as a whole and common culture by all its members. To do this, such discourse makes use of narrative resources, such as religious mythologies originating in Africa and their textual and oral referents. Those narratives aim at projecting a discourse of national cultural integration that forms a whole whose parts originated in Cuban culture’s syncretic processes. They structure a discourse of national integration of a syncretic culture that can be identified in the artistic experiences of Cuba’s historical avant-garde and the negrista and indigenista literary movements of the 1920s and 1930s, that went on well into the 1940s. There are references in literature and visual arts in which the African-ness of Cuban culture springs from an idealizing and romanticizing of its African components carried out by local intellectuals. Some of its subjects, and the artists who develop them are:

A national vision (Cundo Bermúdez, Mario Carreño, Víctor Manuel, Carlos Enríquez, Mariano Rodríguez, René Portocarrero).

Nationality as ethnos (Roberto Diago, Agustín Cárdenas).

Visual poetry (Agustín Cárdenas, Roberto Diago, Wilfredo Lam, Manuel Mendive).[14]

2. Entrancement and contagion

It occurs when artists consciously adopt representational systems characteristic of African cultural traditions, such as oral historical narratives, ambiances and special experiences, and link them to their existential and philosophical concerns. This gives rise to art as a tool for understanding the world that operates much like ritual practices.

Such forms of interpretation imbue artistic projects with a marked metaphorical character. They also use ritual environments to provoke reflection on human existence, and symbolic elements and mythological readings as guidelines to interpreting and decoding the world (starting from these symbolic associations). Finally, they create magical objects by conceptually associating the materials used in artistic practices to those found in ritual experiences, in order to produce magical states and trances of spiritual communion through suggestive and associative interpretations of such materials and those found in Afro-Cuban religions. Among its subjects, and artists who work on them are:

Driven by the Other (Ana Mendieta, Manuel Mendive, Ricardo Rodríguez Brey, María Magdalena Campo Pons, José Bedia, Juan Francisco Elso Padilla, Santiago Rodríguez Olazábal, Marta María Pérez Bravo, Juan Carlos Alom, René Peña, Luis Gómez, José Ángel Vincench, Omar-Pascual Castillo, Belkis Ayón).

Spreading suggestive forms (Ana Mendieta, Manuel Mendive, Ricardo Rodríguez Brey, José Bedia, Santiago Rodríguez Olazábal, María Magdalena Campo Pons, Luis Gómez, Omar-Pascual Castillo, José Ángel Vincench, Belkis Ayón).

Dealings of the transcendent world (Ana Mendieta, Manuel Mendive, Ricardo Rodríguez Brey, José Bedia, Juan Francisco Elso Padilla, Santiago Rodríguez Olazábal, María Magdalena Campo Pons, Luis Gómez, Marta María Pérez Bravo, Juan Carlos Alom, René Peña, Omar-Pascual Castillo, José Ángel Vincench).

3. Identifying the individual and the collective

This problematics takes place when artistic endeavors are aimed at satisfying questions related to existence, the human condition and the work of art as an analytical instrument, by using representational forms and manifold cultural traditions –that is, by hybridizing different visual languages, thus giving value to the mixed character of the artistic product and its processual and ritualistic (performative) quality, concurrently with international artistic problematics and the issues that condition Afro-Cuban religious variables. It is thus that the work is assumed as a therapeutic and reflective tool vis-à-vis the human condition and its accompanying social, historical and cultural problems. This problematics essentially concerns reflective processes that take place in representational practices related to knowledge and language forms that belong to the cultural traditions that gave rise to the Cuban nationality.

EXPRESSIVE TRADITIONS

This text focuses on the expressive or distinctive elements of African cultural traditions present in the visual arts of contemporary Cuba. What distinguished the Caribbean –and Cuba is an integral part of that place where the whole world unites– during its first historical phase, which happened between the 16th- and the 17th-centuries, was the creation of a specific consciousness and a traditional popular culture, where ethnic awareness preceded national identity. It is in the Caribbean where a new concept of ethics, metaphysics, rhetoric, a sense of drama and of belonging to an American region –and not to a European or African one– were developed. More than a heritage, the African component was a force with a value of its own that helped people coming from Africa to confront the polyglot history to which they were transplanted. In the last instance, it also helped them to adopt a different history and to define a unique individuality within their new environment.

We may group carriers of African expressive traditions within two periods:

1. The pre-national era (early 19th-century)

What characterized this period was the existence of cultural spaces of resistance within the capitalist mode of production developed in Spain, which basically exploited sugar plantations. These economic units also acted as spaces where socialization and cultural interaction between diverse ethnic groups transplanted from Africa took place. This dynamics allowed the defense and preservation of African essential values, mores, traditions and legends, and the reinterpretation of these cultural references in a new context and under conditions of slavery and hard labor.

People from different African groups started a process of cultural exchange and developed the ethnic solidarity that their marginal condition demanded. Such exchange and solidarity gave rise to the main Afro-Cuban religions. This process of functional integration generated a shared sense of anxiety and socialization channeled through the common economic identity of people of African descent –either slaves or emancipated but marginalized individuals. It is worth noting that the plantations were also places where a process of “deculturation” took place: a conscious effort to deprive a group of people of their culture and identity with the aim of better exploiting them and using them to exploit available natural resources.

Deculturation implies a distancing from important cultural elements in a group’s everyday life, such as original names, sexual patterns, diet, types of lodging and clothing styles. It also leads to separating them from their music and religion, and involves the compulsory adoption of an alien language and external modes of conduct.

2. Post-slavery (from the abolition, around 1820, onwards)

During this period, there was a massive migration of newly-liberated slaves from the countryside to the cities, where they started participating in a socioeconomic space that, although limited, allowed them to sustain themselves and accumulate some capital for the first time. This generated in them a sense of belonging to the Caribbean, a physical and geographical area, and to expect a safe future within the nation. As a result, the period produced a bonding socio-religious consciousness that gave factual powers an advantage over the individual, who was perceived to be at the service of the group.

This collective consciousness originated with the establishment of the region’s main religious systems (like Palo Monte, Santería, Arará and Abakuá), and of organizations such as the Cabildos de Nación and some secret societies reproducing African social organizations that used to have a similar function. The cabildos were organized along ethnic, religious or linguistic lines, and resulted from an empathic and historical affiliation between several ethnic and cultural groups, but it must be noted that they also served as mechanisms of deculturation.

Transplanted and displaced African cultures developed a religious and philosophical system with a strong and highly performative esthetic component involving music, drama, literature and visual arts. From that starting point, a series of myths and ritual practices provided a framework for new concepts about existence, life and death, social organization, history and the gods. Visual language, for example, keeps a ritual and referential character that may be observed in “firmas” or sacred writings. These function as means for reproducing religious and philosophical knowledge. Such graphic representations take the form of pictograms that include figurative elements (like moon, serpent, woman, sun and skeleton) and geometric symbols (among them, squares, spirals, circles and arrows). This visual language also incorporates tridimensional objects that form part of a ritual context and contain symbolic elements evoking the strength of nature. They also signal the links between believers and these cosmological representations and manifestations.

Written literature gleaned ritual procedures and cosmogonies (notebooks of celebrants known as paleros and babalawos), thus establishing a direct relationship with religious oral traditions. It is a documentary source of cultural memory, registering episodes about the origin of kingdoms and cities, wars, ethical systems, the relationship between the individual and the community, and visions on the world and nature.

In everyday language, cultural influences can be detected in the textual appropriation of voices that come from African tongues (with altered pronunciation). There are, for example, certain rhetorical forms, such as “Oye-oye-oye, ve(n) acá” (“Hear-hear-hear, come hither”), used for communicating something confidential; “Mira-mira-mira! ¡Qué bárbaro, tú!” (“Looka here-looka here-looka here! You’re something, man!”), preceding a comment on any subject, or “Okondo, lazo, lazo, lazo Boco” (“Okondo, lasso, lasso, lasso, Boco”), a formula for invoking the ireme (in abakuá tradition, a mythical or spiritual figure generally represented, in a negative manner, as a diablito or little devil).

A VISUAL LANGUAGE

There are some problems related to visual language. I will proceed to briefly discuss some instances, although many of these artists deserve a more extensive study, since they have made a significant contribution to 20th-century art. In discussing the problematics of African cultures within Cuban art, we must start by recognizing that a basic African element is part of the intercultural substratum of the whole Caribbean basin, and that it manifests itself in some specific content areas.

In this instance, I will outline three of the main subjects that have a direct bearing on the oeuvre of Carlos Luna: ethnological representations; entrancement and contagion, and the chronicles of memory –especially because his works cannot be easily classified within any of these categories. Their fluidity prevents us from placing them exclusively within the esthetic and conceptual coordinates that I will now describe. And it must be said that this is something that the artist shares with several other Cuban creators, although the process of “creative fluidity” as a paradigm and artistic praxis is more evident in Luna’s production.

Ethnological art has two significant components:

1. Ethnic visualizations. This refers to the presence of African elements in the origins of Cuban culture and what we may call the “Cuban cultural imaginary”, which runs from José Martí to the present. The influence of African cultures is more clearly appreciated in paintings and sculptures, drawings and prints of several important artists. These representations frequently recreate a mythology that has been preserved in oral and local traditions. They were developed by artists such as Víctor Manuel, Cundo Bermúdez, Mario Carreño, Carlos Enríquez, Mariano Rodríguez, René Portocarrero, Agustín Cárdenas, Manuel Medive, Roberto Diago, Wifredo Lam (in his iconic, “La jungla” – “The Jungle”), and Roberto Diago (in “Mujer”). The latter uses an expressionist language echoing forms and colors originally developed by grandfather Diago, and also explored by contemporary artist Roberto Diago (grandson) in “La energía del mundo” (“The World’s Energy”).

We are dealing here with a neo-baroque imaginary, as Lezama Lima would call it. It is full, saturated, a perfect example of Cuban horror vacui, characteristic of ritualistic spaces but reinterpreted through pictorial language. Other artists that may help us better to understand this subject are Jesús Rivera (“Ogun-Changó” and “La Virgen del Cobre”), Belkis Ayón (“Mi corazón” – “My Heart”– and “Te amo” – “I Love You”) and Elio Rodríguez (“La jungla” – “The Jungle” –, “Pareja en el solar” – “A Couple at the Estate”– and “Bodegón” – “Still Life”).

2. Visual poetry. It deals with the ways in which transplanted African cultures were synthesized and became points of reference within the Cuban context. In other words, African cultures constitute themselves into an expressive factor with a thematic and allusions that allow us to identify the typological elements, the philosophical content and the cosmological visions of Afro-Cuban religions. Examples abound: José Bedia. Ricardo Rodríguez Brey, María Magdalena Campos Pons, Santiago Rodríguez Olazábal, Manuel Mendive, Marta María Pérez, Luis Gómez-Anderes Montalván, Juan Francisco Elso Padilla (“Hacha de Changó” – “Changó Ax” – and “Pájaro que vuela sobre América” – “A Bird Flying Over America) and Belkis Ayón (“¿De dónde eres tú?” – “Where Are You From?”).

Entrancement and contagion is the second space to be outlined. Its most important concern is what we might call the material world’s instrumentalism. It occurs when an artist adopts mechanisms and systems for representing objects based on Afro-Cuban religions. In these cases, the creator also embraces their sense of ritual, their materialism and their conceptual metaphoric character. Among the artists exemplifying this are: Juan Francisco Elso Padilla (“La serpiente y el maíz” – “Maize and the Serpent”), Ana Mendieta, Ricardo Rodríguez Brey, José Bedia, Luis Gómez, Geysel Capetillo (“Recurrencia (Fragmento)” – “Recurrence (Fragment)”), José Ángel Vincench y Andrés Montalván (“El dulce encanto de la vida” – “The Sweet Enchantment of Life”).

The chronicles of memory. Its main component is what I consider to be a kind of artistic practice of philosophical reflection. Artistic works within this category are devoted to questions relating to the human condition, analyzing the world through knowledge and notions of a reality determined by magical-realist thought and the artistic morphology of Afro-Cuban religious and mythological traditions. Examples are José Bedia, María Magdalena Campo Pons, Manuel Arenas, Juan Francisco Elso Padilla (“El poder de la guerrilla” – “Guerrilla Power”).

This type of work exemplifies art as a process directed at apprehending the world, as a spiritual edification equaling those of Afro-Cuban religions. It also searches for a magical state of spiritual communion with the world, through the ritualistic use of war councils. Some of its elements are blood, mud, wood, personal objects, pepper, fabrics, volcanic ashes, wax and mirrors. It is exemplified by Belkis Ayón (“Reivindicado” – “Vindicated”), Andrés Montalván (“Noble corazón – “Noble Heart” and “Límite invisible” – “An Invisible Limit”) and Luis Gómez (“Bad Fundación”).

THE WORKS OF CARLOS LUNA

Carlos Luna adheres to very concrete criteria regarding pictorial language, and these criteria must be understood by using specific examples taken from his artistic trajectory. His conception of a hierarchical and orderly reality allows him to attain an absolute existence of spiritual achievement. His insights spring from the knowledge possessed by the initiates of the Secrets of Ifá and by the Olwos –Babalawo-Yoruba priests. In this way, the cosmogony that Carlos strives to reproduce is a reflection of a certain knowledge, or, better yet, of the notion of a certain knowledge. The artist considers “empiric” reality as something of an approximation to a pre-written absolute, formalized and made evident in the Yoruba system of divination known as the Rule of Ifá. Yet, Luna believes that this system per se cannot achieve “absolute reality”, since only the individual, through his or her own personal decisions and his or her sense of responsibility towards him/herself will give it its full greatness. The just greatness of Yoruba cults lies in having respect for free will. They cannot judge; they only signal.

In this sense, reality is presented as something absolute that aims at achieving the individual’s spiritual emancipation, which can only be reached through diverse esthetic and conceptual coordinates.

Carlos’ works may be conceived to exist between the praxis and the experience of a religious system devoted to generating knowledge, just as Ifá’s divinatory tradition in Yoruba cults does. It is a creative-technical process imbued by Western academic art, with quasi humoristic and critical graphic references to a social and cultural reality. Luna characterizes such reality as a sensual one, defining Mexican and Cuban local cultures. It is thus that the creation of pictorial images may be considered the artist’s utterance that more closely gets to formulating a conception of “reality”.

Luna believes that pictorial images are more than mere approximations to the material object that they mirror or depict. He doesn’t conceive of material objects as existing in a unique social context. Instead, there are only experiences, memories, emotions in multiple, parallel and alternative contexts. Therefore, from the Yoruba conceptual point of view, derived from Ifá knowledge, there are only “moral archetypes, behavioral rules, social order and spiritual emancipation”, whereas, within the Western context, attention is bestowed on esthetic preconditions of pleasure, beauty and perfection.

It is thus that the language of Luna’s paintings becomes a continuous exercise of approximation and proximity between two realities and temporal spheres determined by contemporary society and living. The (conceptual) notion of reality exists as a possible balance between one dimension methodically outlined on Ifá’s procedures –known as odduns– as a conceptual “reality” of a religious nature, on the one hand, and a dimension charted by ethical precepts typical of (and typified by) modern Western culture, on the other. This leads to Luna’s paintings becoming multiple points of entry to a much more complex reality –double, dialectic, hierarchical–, and stop being images with certain qualities that might be used to construct a reality opposed to the one represented by the image. They are the equivalent of Buddhist mandalas, veritable pictorial mantras. Among the objects thus handled by Luna we might mention tables, cocks and guajiro field workers.

Unlike Plato, Carlos Luna does not reject pictorial imitation based on visual illusionism. In his case, the element that determines and characterizes the painting’s language is not an optical experience devoid of “truth”. As I mentioned earlier, his notion of reality is a point of entry, a gaze, a window into knowledge paradigms and diverse cultural realities.

In Luna’s gazes, we find the simultaneous effect of Western esthetic codes present in the language of painting, such as plays with lights and shadows, a resourceful use of perspective, complex compositions, color combinations suggesting quasi iconographic forms –typical of abstract painting–, and of ethical and philosophic-spiritual principles sketched by Ifá Yoruba literature and religious exegesis, or in local popular knowledge.

In this respect, the notion of “gaze” is much more than a suggestion or an arbitrary evocation, an inspired and illusory perception of reality, and it is certainly not a counterbalance of the reality it represents. In Carlos Luna’s case, the sense of perception is not driven towards understanding reality as experience and optical translation. Rather, his perception is characterized by a complete adhesion to conceptual notions that correspond, not so much to an external or imagined reality, but to an intentional creation with solid cultural foundations and a unique (or unifying) artistic sensibility.

We might conclude that Luna’s artistic creativity incorporates a “visual imagination” that makes us feel a different attitude, a certain awakening of symbolic meaning associated with the artistic act.

Just like in “El gran mambo” (“Big Mambo”), Luna insists in narrating a personal history that becomes a chronicle and does not depend on sensorial impressions. The artist tries to articulate a poetics not wholly related to the world of impressions. The elements depicted in this work –such as eyes, scissors, knives, open mouths, shoes, legs, flowers, cocks, coffee pots, genitalia, telephones, hands, a Yoruba deity (Elegbá), airplanes and verbal supplements– are not mere physical and optical references to such objects, but rather a way of renaming them. This is related to the fact that Ifá’s power resides on the tongue, on the power of renaming things, of restoring a soul to them.

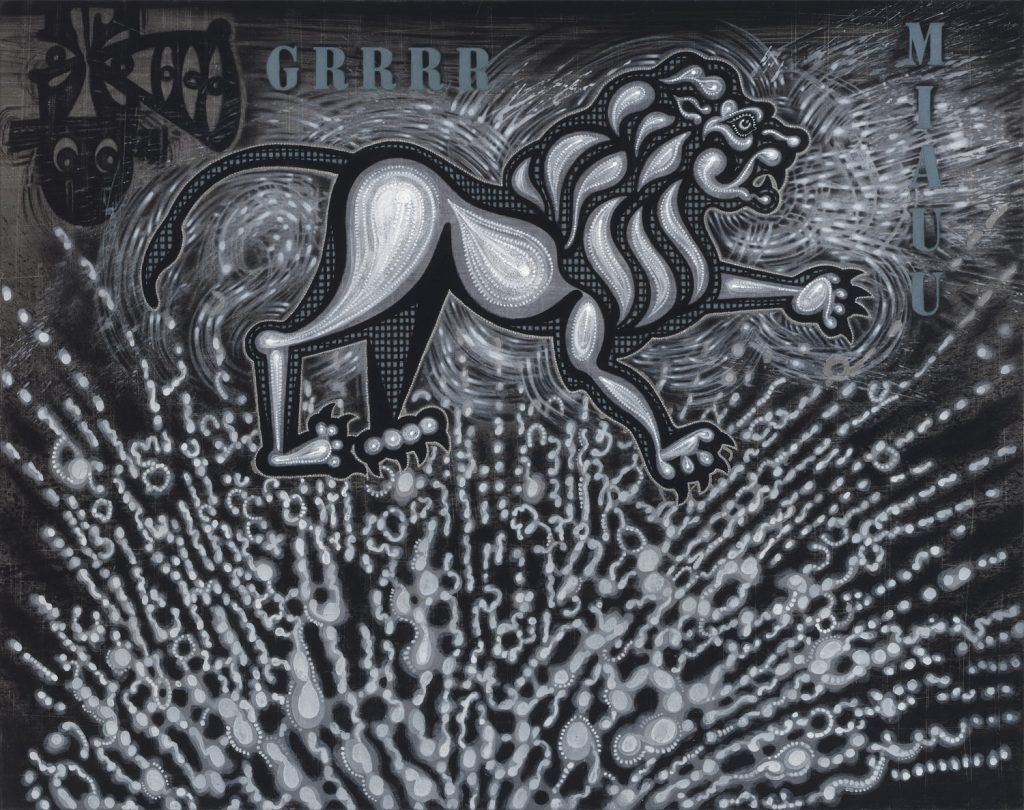

There are other works that exemplify this symbolic narrative, among them “Encuentro nocturno” (“Night Encounter”, 1999), “Es tarde, ya me voy” (“It’s Late, I’m Leaving”, 2004), “Uff” (2007), “Hello, guajira” (2008), “La cosa negra” (“The Black Stuff”, 2008) and “Empingated” (2008).

Luna believes that these objects possess a certain autonomy, and their depictions deliberately allow us to gaze at the other side of representation and see them in a different light, as symbols evoking personal memories and experiences, rather than as physical references or tangible objects existing within the realm of reality. Thus, a sewing machine alludes to home life and domestic spaces, while a grandmother symbolizes familial continuity and transcendence, and also filial love.

Seeking the other side of representation means approaching things from a unique, personal and somewhat skewed perspective, so that the sewing machine can be viewed as a reference to mechanical recollection, the randomness of memory or the violence imposed by absurd sociopolitical circumstances. It may also allude to an act of recognition of memory, of our scattered remains, of the places we have emigrated to. In a similar fashion, the steam engine in “Robo-ilusión” (“Theft-Illusion”) evokes a nostalgic past, a yearning for childhood, and more indirectly the passage of time, the act of judging things from the distance imposed by time, and travel as a metaphor.

Accordingly, the airplane in “Muerto en vida” (“Living Dead”, 2004) stops being a symbol and becomes an ontological reflection on the loss of place, leaving one’s homeland and disappointment in the country where one was born. The airplane thus becomes a source of reflection on personal displacement and on the impotence felt before life’s conditions.

For Luna, that kind of gaze is only attainable from the distance, from a sense of impossibility imposed by reflection, as something seen after the fact, constrained by its very framing and by the distance imposed by time. Other ontological works are “Árbol grande, Guajiro yo” (“Big Tree, I Guajiro”, 2011), “Bruca manigua” (2004), “Isla sola” (“Lonely Island”, 2006) and “Aquella pinche circunstancia” (“That Wretched Circumstance”, 2007).

“El gran mambo” (“Big Mambo”) tries to recreate reality as a personal “absolute”, almost interchangeable with those of other people. It is a kind of sublimation of a travelogue that chronicles a departure from Cuba in the 1980s, on to Mexico and to an eventual arrival at the United States in the new century. In this narrative context, transcendence implies self-exploration, getting to know oneself among a sea of transformations and encounters, using travel as a metaphor, insisting on ontological experience and processes of change, rather than on the physical sojourn.

It is difficult to ignore the intellectual transformation that takes place in Luna’s works, and his intellectual attitude towards art, especially in his later stages, where experimentation becomes more evident. That is what happens in his tapestries, the skirt he designed for Daniela Gregis, and the metalwork that he produced in collaboration with Magnolia Editions in California. The experimental bent is clearly visible and suggests new questions and new conceptual approaches referring to form as language structure. Within the subjects developed during this new experimental phase, the artist himself stands out. Luna becomes the focus point of his conceptual, political and spiritual concerns in an attempt at penetrating the mysteries of creating images and narrating diverse, parallel stories, woven by time and memory. Creation becomes the perpetual machine of a new being liberated by art. Made free by art.

____________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bozal, Valeriano (1996). Los orígenes de la estética moderna. Madrid, La Balsa de la Medusa.

Castellanos, Jorge e Isabel (1998). Cultura Afrocubana. Vol. 1, Miami, Universal, 1988.

Deschamps Chapeaux, Pedro (1970). El negro en la economía habanera del siglo XIX. Havana, UNEAC.

Moreno Fraginals, Manuel (1964). El Ingenio; Complejo Económico Social Cubano del Azúcar, Vol. 1, Havana.

_____________________ (2000). Class lecture. “The Spanish Caribbean, 1860-1940”. Yale University. February 2.

Thompson, Robert Farris (1984). Flash of the Spirit. Afro-American Art & Philosophy. New York, Vintage Books.

___________________ (1992). “Dancing Between Two Worlds, Kongo-Angola”. Culture and the Americas. New York, Caribbean Cultural Center.

___________________ (1999). Class lecture. “New York Mambo: Microcosm of Black Creativity”. Yale University. September 9.

___________________ (1999). Class lecture. “Communication from Afro-Atlantic”. Yale University. September 23.

[1] Manuel Moreno Fraginals (2000).

[2] For starters, we must say that such pluralism is explained by the fact that “it wasn’t a single African or Asiatic people that got displaced to Cuba, the Americas or the Caribbean”, but rather many peoples and on many instances.

[3] Thanks to Havana’s thriving economic and demographic development, and to its oligarchy’s ascent, it is not difficult to understand how certain attitudes of deep regionalism took root in provincial societies. On the positive side, such regionalism can be interpreted as a love for the local homeland (city or town) that does not extend to the wider country (fatherland).

[4] Manuel Moreno Fraginals, Ibid.: 121.

[5] Manuel Moreno Fraginals, Ibid. “Patria (fatherland), a word that Arrate constantly repeats, evokes the Romans’ love of country. Yet, in the sense that Livy (Titus Livius) uses it (let’s not forget Arrate’s classical upbringing), it does not only relate to place of birth. Rather, it is a term associated with family, society, freedom and happiness”. The writer concludes by quoting one of the best Cuban sonnets of all time: “O, beloved Fatherland, Noble Havana, enlightened city!”.

[6] Ibid.: 123.

[7] Ibid.: 125.

[8] Pedro Deschamps Chapeaux (1970: 31).

[9] Ibid.: 89.

[10] Ibid.: 43-44.

[11] Robert Farris Thompson (1992: 2).

[12] Robert Farris Thompson. Ibid.

[13] Robert Farris Thompson. Ibid.

[14] In a sense, this symptom manifests itself at skin level, in a phenomenological, transitory, superficial and literal (rather than literary or fabulist) way, but it does not go further in questioning our identity, but simply exposes it –not a small deed, considering the Western-reinforcing context, where “blackness = African” was repressed.

Back to WRITINGS

Back to WRITINGS