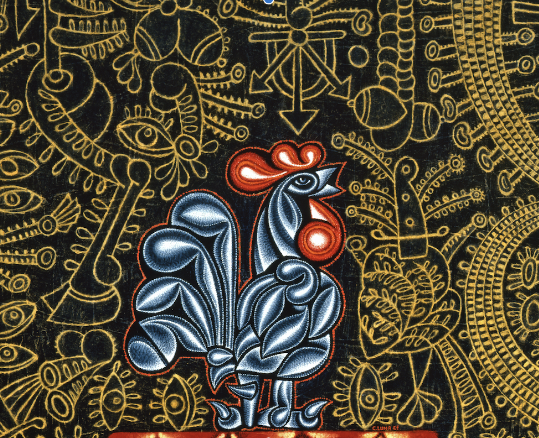

A CONVERSATION WITH CARLOS LUNA. THE BIRD-OF-PARADISE AND ITS SHADOW

JR: How did Carlos Luna, the painter, emerge?

CL: I’m going to confess something that I haven’t made public before. Only a few people know about this situation; however, it may help to understand the course of my art. My father suffered from a kind of schizophrenia, and I remember in my childhood, during a period of crisis in his disease, he drew on the walls of his room, especially near the bed. This was something he apparently needed to do to relieve his anguish. I was about five or six years old then. I was never able to observe him in the full action of drawing, but I contemplated the result of his renderings when my mother wasn’t looking, and I could to slip into the place. There were clay brick walls plastered with cement, about two and a half meters high and three wide that my dad covered with pencil and crayon images. This was my first encounter with the act of visual expression… Figures spawned by the urgent need to get things out from inside. Now my first contact with fine art was in my grandfather’s tobacco shop, where Grandmother had a collection of very curious images of Christ. Of these I remember the Christs by Matthias Grünewald,[1] Andrea Mantegna,[2]and Velázquez. She also had images of people beatified in the Romanic period, in particular the Beatus of Liébana.[3] These were my first experiences with art, and from them my first artistic stirrings coalesce and emerge.

JR: Do you remember something about your father’s drawings?

CL: They were very primitive. Perhaps this is what later predisposed me toward an interest in the outsiders,[4]and this magnetism that has always influenced my taste and that has its roots in the fascination with my father’s drawings.

JR: But, in addition, your entire work has a tremendous Caribbean and rural influence…

CL: Good, because above all I’m a guajiro,[5]and to the extent that I have painted and immersed myself in the introspective process of creation, I realize that my guajiro status is obvious. This definitely marks my work.

JR: Do you regard your painting as costumbrista?*

CL: No, because I don’t seek to illustrate rural customs in a certain way. Further, I like the city and the benefits it provides. My work, I believe, goes beyond Creole picturesqueness and becomes a chronicle and reflection of various aspects of culture and its idiosyncrasy. It is a mix of things. In many cases they are only excuses for aesthetic and formal studies.

JR: Would you dare to classify your work?

CL: It’s difficult. I feel that I am a translator in conjunction with diverse cultural and even racial references. I don’t see myself as part of a specific trend. Within me there intersect genres and epochs. For instance, it is true that what predominates in my works is representation, but there are visible zones of abstraction.

JR: In your discourse there are well determined signs that are reiterated. Is this a technique articulated with premeditation or one of obsessive involuntary recurrences?

CL: There are two things. Of course I have a glossary I turn to and I assemble visual phrases, but there is semi-unconscious moment, if you will, that is like a trance wherein the hand responds to what is spontaneously flowing. I am different from an outsider because I quickly lend an order to these obsessions. So there are indeed codes that are repeated, and I am unaware. I come to the painting with a general idea established in the sketch, and in the execution, accidents of creation are produced, and some of them are intuitive.

JR: Does the painting or the title come first?

CL: The title often comes first. The phrase or word can condition the course of a project. On other occasions both appear simultaneously. Take the example of my painting El Gran Mambo. I was immersed in the creation of this piece which is like a gigantic rhythmic detonation with a prodigious melodic narration, when I remember hearing something by Pérez Prado[6]performed by Benny Moré,[7]and the idea of the title suddenly came because it was related to what I was painting, a sort of monumental mambo.

JR: I once wrote that this painting, El Gran Mambo, is your masterpiece; it is the summation of your experience as a painter. There is manifest in this work a closeness to Picasso, Lam, and Mexican muralism… Is that true?

CL: No doubt there is [in this painting] a lot of the magic of Mexican popular art and muralism. More than Picasso, it contains is a great lesson from the apocalyptic passages of the Beatus of Liébana, from whom Picasso also draws inspiration. Also, there is a touch of Bosch, and the assimilation of Lam is inevitable for any Cuban artist.

JR: I also see in El Gran Mambo, and in some of your other works, something of the narrative disjointedness of the Latin American literary boom.

CL: Definitely. Considering this in depth, connections can be established with this literary phenomenon.

JR: What endures of Carlos Luna from the 1980s and the 1990s?

CL: First of all, I’m still the same Cuban. The same keen desire of creating a career with its own identity continues. The same approach of being contemporary while standing on the shoulders of tradition. Of course I have evolved, I have integrated the journey and information gleaned from the decades gone by.

JR: You left Cuba for Mexico?

CL: Yes, in September of 1991.

JR: What motivated you to leave Cuba?

CL: I don’t want to get involved in political topics, but I can tell you that my decision is based on the need to express myself with total freedom. In Cuba you can express yourself while you don’t deal with a touchy aspect that irritates the government. For my rebellion there in Cuba, I always felt I was trapped; I wasn’t welcome in the established structures of the official culture. I got everything I could out of my work in Cuba. There I had a successful career with prizes and distinctions. I can’t complain, but I could not stand the status quo.

JR: Of your twelve years’ residency in Mexico, what lesson did you feel most strongly?

CL: Especially Rufino Tamayo. Tamayo influences me, above all, in the ideas, in the way of perceiving art, in his attitude of being contemporary while standing upon tradition. Rufino was a very disciplined artist and very firm in his beliefs―above movements, trends, criticism, and curatorial opinions. He was an artist independent of all this. He was a paradigm for me before leaving Cuba. By then I had read a text by Octavio Paz about Rufino, and what I wanted to do was clarified in those paragraphs and in his painting. In general, Mexican art has a fundamental importance in my body of work. There are other Mexican masters who strongly appealed to me, and I can mention José Guadalupe Posadas, Antonio Ruiz el Corzo, and I personally knew José Luis Cuevas, Juan Soriano, Francisco Toledo, Irma Palacios, and Miguel Cervantes, who was a friend and close advisor.

JR: Do you think at this stage of your career you have been endowed with a language and characteristic iconography?

CL: Of course. I think that people can easily recognize my work by the personal way I express my universe.

JR: Where does the routine end and experimentation begin in your work?

CL: They coexist. I use traditional means, but in every piece there are new approaches. There is a constant search for new materials or tools. Brushes with a specific use I use for other variations. Techniques I followed in one way I now do in another. Many times experiments are a result of observations derived from the work of masters in painting, and on other occasions the piece’s requirements demand a new solution. In each painting, there is a moment of experimentation, on a level with the painter’s discipline and the methods learned in the academy. Painting involves a lot of science because you can’t achieve a result without beforehand respecting certain processes. Experimentation can surprise you at any stage of these processes, and one has to pay attention to this encounter with innovation. Otherwise, you don’t evolve.

JR: Have you undertaken a painting project with one intention that has drifted toward another outcome?

CL: Yes. In this sense, I am always open to how an idea can shift and the route of improvisation. I work with a preconceived plan and with control, but also with a tendency to flexibility and changes. This is natural in art.

JR: Do you have some ritual that proceeds or forms part of the creative process?

CL: Well, yes. I have a type of ceremony that begins when arriving at my studio and changing into more comfortable clothes. I immediately put on music that gets me in the mood. Music is like the formal opening of the workshop. Often I light a cigarette and from my chair reflect about the piece I am going to work on. Since the day before, the palette, the brushes, and all the tools I use have been clean. I work simultaneously on various paintings, and during the small prelude with the tobacco smoke is when I determine which will be the piece of the day. I then have some moments of looking at the designated piece, examining what has been done and what remains to be done. Music is very important for me. I listen to traditional Cuban and Mexican music that immediately connects me to memories, details, and significant aspects of my life. Then, the ideas flow and I begin to paint.

JR: In the anecdotal material that gathers in your imagery and in the eroticism that at moments you recreate there is a perceptible predominance of the masculine, that is, there is a palpable presence of machismo. Do you think about it ahead of time or does it spring involuntarily?

CL: It comes spontaneously because I was born and educated in an essentially male chauvinist society. The unusual thing is that although there is more work with the masculine in my art, the moment the female figure appears, this figure becomes predominant. The female figure I depict as all-encompassing, or if she appears alongside a man, I make her of a size proportionately greater. I believe that in the Cuban case it is necessary to determine the woman’s responsibility in this way of seeing things. Mama educated all of us to operate in a male chauvinist society. I note that it is a terrible factor that characterizes Latin American society. And machismo in Cuba is extreme. It is like a concealed fear and at the same time powerful that the woman is recognized for the true role she plays as shaper of generations and indispensable arbiter of social life. In my work possibly can be found this internal conflict of the Latin American macho. This battle of the sexes that flows more or less consciously in the psyche of our continent’s men. At times, in my painting, I try to ridicule or satirize the topic or expose it in all its rawness. Whether I am right or not, it is part of my internal struggle. Yes, I can fully affirm that I greatly respect women, and my companion can vouch for that, and although I am not a pro-feminist, I do attempt to defend their qualities, their interests, their needs, and their concerns. I believe that women have a capacity for resistance that men lack; they have a capacity for autonomy and leadership which we lack. Women, generally, are better prepared to manage among so many other things. I consider that in the case of male artists, the selection of the woman with whom he is going to form a team is fundamental in his career.

JR: There is another burning topic related to your uniqueness, though it is a phenomenon spread in contemporary turbulence and that shows in your painting through aggressive intent and the presence of weapons. I refer to violence…

CL: My childhood was spent in a peaceful country town, where the most natural thing in the world was to kill an animal for daily survival; this could be a goat, a pig, or a hen. There were acts of violence that formed part of the rigors of daily life. However, when I moved to Havana to study, I discovered urban violence, and it became commonplace to see people carrying guns for self-defense, or because of the need to intimidate their fellow men. In Mexico I experienced this phenomenon personally, and my work has not been nor will it be detached from this phenomenon that is unfortunately part of the everyday modern life.

JR: Do you feel bound to the path chosen by you in the development of your work?

CL: You know that question seems to me to be somewhat one-sided. I am open to shifts, truly, but I feel satisfied with the means and the world that I recreate. Throughout my years as an artist I have gone one step at a time. Neither abrupt transformations nor great leaps have interested me, all the while reviewing good choices and bad choices. I spend my life seeking to give myself feedback, reconsidering technical and conceptual solutions. When in solo exhibitions I have had to chance to contemplate sequences of works that I have created over different periods of time, I notice the evolution, and the different way of resolving the challenge of a painting. There is recycling with innovations. With viewpoints that maneuver according to experience.

JR: Now that you have mentioned the topic of exhibitions, I would like you to speak about the MOLAA project. Who is curating it?

CL: Cynthia MacMullin, Vice President associated with exhibitions at MOLAA, and Idurre Alonso, curator of MOLAA. They are in charge of the itinerary of the two shows: one in MOLAA with seventeen works and another in the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center in Washington, DC with three or four pieces more. Cynthia is American, and Idurre is Spanish. Both were familiar my work and were interested in bringing it to these spaces. The same night my exhibition opens in this institution, a major exhibition of Lam opens here, as well. Imagine how I feel having this moment marvelously synchronized with a master.

JR: What specific thesis has the curatorship proposed?

CL: Well, at MOLAA they have proposed a collection of artists born in Latin America, whose works are especially resolved by traditional methods. My work fits perfectly within that criteria.

JR: The group of pieces selected have a tendency toward your most baroque and exuberant facet, and I’ll name a few titles―in addition to El Gran Mambo, such as Café Con Con, Misa Negra, El Rapto de la Catalina, Bruca Manigua, Hello mi amiga. To what do you attribute this choice? Is it related to parallelism with Lam?

CL: Not at all. This is a prominent feature of many of my paintings. Frequently I inundate the areas of the canvas with a hodgepodge of colors that arise from an incessant flow of ideas or of formal intentions. At times I feel cramped. It is something innate in me; it forms part of my insistence on mixing dissimilar things. In the case of establishing a connection with Lam, it would be better to look at it as contrasts, because the painting of the maestro, Lam, has a great deal of metaphysical content while mine is more attached to earthly things.

JR: I also notice a variety of techniques and media in the selection… This was the curatorship’s choice?

CL: Yes, that’s how Cynthia and Idurre decided; they made the entire selection of the works. There are things representative of the last three or four years and pieces of my artistic production in Mexico, from the first visits Cynthia and later Idurre made to my studio, they emphasized that my passage through Mexican territory is critical to understanding my discourse. The curators are very connected with my perspectives as an artist and they share them, concur with their concepts, and use my work to reinforce them. I believe that they take into account the great traditional energy of Latin American visual arts and, it seems, they have found a compact example of it in my work. Visual thought in the continent has a contained and stunning force, and a deeply indigenous identity. They think that my insertion in Mexican culture and the hybridization with the Cuban background has created a fresh way to create images.

JR: In the present context of your residence in the United States, do you feel yourself a Cuban artist, Hispanic (according to the bureaucratic classification), or Latin American?

CL: I feel like all of them at the same time. Whoever exhibits or doesn’t exhibit as a Cuban, doesn’t make me feel less Cuban. Whoever exhibits or doesn’t exhibit as a Hispanic or Latin American artist, doesn’t affect this belonging, either. But also, with my subject matter of local color, I also feel I’m an American artist. I am proud to be a citizen of the United States and thankful for what this country has given me. I also feel, at the same time, something of a citizen of the world. I believe that this is a sentiment quite familiar to Cubans scattered across the globe.

JR: What is your debt to American art?

CL: I am indebted for certain aesthetic influences and the civic and entrepreneurial sense of the artist. Artists in the U.S. have a pragmatic sense of fighting for their art. They seek quality material and what is most adequate for their projects. They legally protect the artistic result and document their work, respect others’ work, and develop the link with the market.

JR: And from the purely aesthetic viewpoint?

CL: There are American artists I feel very drawn to, such as Susan Rothenberg, Philip Guston, Elizabeth Murray, Basquiat, Jasper Johns… and the outsiders. In the American culture the outsiders occupy an important space. And I feel close to Martin Ramirez, Eddie Arning, and Bill Traylor, among others. In them I detect identity, originality. They have an inimitable DNA. They were capable of discovering and marking their own territory of expression. The outsiders live so overwhelmed by the exterior noise that they live submerged in themselves, and their creations are simply the result of what they throw to the exterior world from their respective labyrinths. Their art conveys an exclusive language and personality.

JR: What does the artist-museum nexus signify for you?

CL: The ideal space for the categorization of an artist’s oeuvre is the museum. The museum’s role is above all to disseminate culture. I learned this from the Mexican masters. They confer enormous importance on the museum space as the Mecca of a creator’s work. Today there are scores of art fairs that operate like a huge trade parties in which the transcendence of a seminar or any didactic event is lost. The fairs become the cover for conducting business beyond the contact with the work of art; they are meeting places for bankers, moneylenders, and real estate agents. The museum is the place that gives priority to the educational and aesthetic value of the work, and I see this institutional relationship as something essential for the artist and for the position his work can occupy within the critical and historical appraisal. I can’t complain in this regard. There are prestigious institutions that have been interested in my pieces, and there they are [housed], thank God.

JR. How do you judge the artist-market interaction?

CL: This is quite a complex issue. The market is a voracious mechanism to and it doesn’t care who you are. You should abide by the law of supply and demand. You have to create art that doesn’t betray you, and at the same time, is a product for the collector’s consumption. It’s hard. There are many ways to link yourself as an artist to the market. There are those who join up with a gallery, and the gallery promotes the artist. I decided to personally assume my management. The buyers who approach me are interested, and they like what I do. My wife helps me with the promotion, and making myself known is something I learned in Mexico that is essential for the creator, to make his creation known.

JR: The market hasn’t treated you badly, and has this threatened your aesthetic?

CL: Not at all. I have done what I’ve felt like in my work. I paint what I desire. My happiest paintings, for example, are ripe with a sexuality that can offend the conservatism of many families, and people still buy them. There is something noteworthy about this: while generating my art I don’t flirt with anybody’s tastes but my own. I am impulsive with what I paint, and I will continue that way. Those who commission a piece do so because they like my work and not because I am willing to cater to them. And I won’t stop tackling themes in a crude or difficult manner to please a buyer. I will keep doing what satisfies me, independently of criticism or the market; in this sense, I am totally irreverent and try above all to be true to myself.

JR: Do you feel what you do is tied to popular culture?

CL: I felt since I was in Cuba and Mexico that I could enrich it in a decisive way. Popular art is a vigorous force of expression. I have the theory that pop culture is the spinal column of all fine culture. In general, I have absorbed any popular expression from around the world, for example, in my town for years they made floats and giant dolls for the carnivals that had an enormous impact, between kitschy and popular that were fascinating, where you found present the sly mockery of power with a great show of cunning and ingenuity at the moment of creating all this paraphernalia. These images left an important influence in me.

JR: Do you understand painting as a more permanent expression?

CL: What is permanent is very relative, what is permanent for one person is impermanent for another. What I can tell you is for a long time they have tried to kill painting. Painting has many detractors, and, nevertheless, it’s still there, lasting. They are detractors due to inability, ignorance, or laziness. I am an artist, and I express myself through traditional means with an emphasis on painting, but foremost, I am a defender of art that is one single art. I believe in the solution of vital conflicts through aesthetics, whatever the means of expression, be it drawing, painting, sculpture, engraving, video, installation, etc. The work of art as art will be defined and resolved in itself. As I told you, I feel comfortable in painting; it is the medium in which I want to develop.

JR: Let’s take another point of the same question. Do you believe in painting as a discursive resource in the contemporary world?

CL: For me the contemporary world is not attached to a medium. This is an error of perception and a manifestation of ignorance, as I mentioned previously. Modernity defines the position that is taken in this context and in the time you happen to live in. I am as contemporary as somebody who does altered photography or video. Today there are many who judge the modernity of artists by the medium they use to express themselves. For me it’s easy: the fact that art requires a powerful capacity of invention fortunately does not mean that every invention is art. Ask the people who now visit the Prado Museum if they would stop going simply because the galleries house neither videos, nor installations, or other conceptual assemblages. And there is the Prado and the world’s other great museums receiving visitors constantly. People are interested in seeing works that leave a mark, and that’s enough. Contemporary life is all that is happening now. This conversation that we’re having now beside this bird-of-paradise is contemporary life. This bird-of-paradise and its hundreds of leaves playing in the light is contemporary. Its exuberance, its showiness, and its calm shadow are contemporary. And it prompts me to paint this bird-of-paradise with its shadow, and I do it in an unusual way. This is, definitely, contemporary.

JR: Do you feel removed from performance art or the installation.

CL: As part of my career they don’t interest me. I have a more purist vision. I prefer avant-garde theatrical or movie decoration to an installation. Or I get more enjoyment out of the monologue of an intense theater piece than from performance art. Which is not to say that I am unable to praise alternate visual creations of high quality, although they appear to me as mediums of expression halfway between more concrete forms of artistic representation. With these forms of expression, I experience seeing them as an attempt to add many things which, a good deal of the time, mean nothing. For example, I wonder about the installations, if they are good, new, and expensive, how come when the art fairs conclude these complex assemblages end up in the garbage because there are not enough reasons to take them home. With what I am saying I am not disdaining these ways of visual discourse today, but I am thinking aloud about the misgivings I have about them.

JR: Your great loves besides painting?

CL: My wife and my children. The family is a compendium of love. Music, especially Cuban music… Animals… Some carefully chosen friends, we care for each other, and protect each other. I am contented to know I am a friend of my friends.

JR: Claudia…?

CL: Claudia is my wife, companion, and confidante. The mother of my children, the one who watches out for their education. The friend who helps me, a partner in work. A harsh critic of my work. The person who keeps my feet on the ground. The advisor. The one who accompanies me in everyday life. My children are the greatest reward. Claudia is an essential part of me. God wanted something to happen between us, so he put her in my path. It’s wonderful that when we bumped into each other, we realized that we had to do things together. We have been together for fifteen years. Sometimes I look at her and I say to myself, she ought to be annoyed from waking up and looking at my face every morning. But here we are, above all the stormy weather, respecting the union that God willed one fine day.

[1]Matthias Grünwald (ca. 1428-1528). German Renaissance painter and hydraulic engineer. He painted mainly religious works, especially dark, painful crucifixion scenes.

[2]Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1431-1506), painter of the Italian Quattrocento. She cultivated the classic human figure in her work.

[3]Beatus of Liébana (? – 798) Monk of the monastery of San Martin de Turieno. Author of, among other works, of a commentary on the Apocalypse that was one of the most renowned books of the Middle Ages on the Iberian Peninsula due to its political and theological significance.

[4]Outsider art: A term coined by the art critic, Roger Cardinal, to describe art created outside the traditional concepts and established cultural institutions and that reflects dysfunctional psychic states, eccentric personalities, or extreme imagination.

[5]Cuban term for the person who lives and works in the country or comes from a rural zone.

*Translator’s Note: A practitioner of costumbrismo, the literary and pictorial depiction of regional customs and manners.

[6]Dámaso Pérez Prado (1916-1989) – Cuban musician and composer, known worldwide for popularizing the mambo, a rhythm created by Arsenio Rodríguez and Israel Cachao López.

[7]Benny Moré (1919-1963) – Considered by many to be among the all-time most important Cuban singers and composers. Endowed with an innate musical sense and a fluid tenor he shone in genres such as the son montuno, the mambo, and the bolero.

Back to WRITINGS

Back to WRITINGS