A “COMPAY” WHO DANCES LIKE AN EGYPTIAN

What relation is there between a Cuban Compay and Amenhotep IV? Between an islander crowing and the god Horus? It would seem an imprudence to match such personages. However, such problem finds its solution on the painting of Carlos Luna. Al least in the series he is showing us now, the relation mentioned is closer than that imagined.

Let us remember that the primitive pictorial representations, those that reflect the early civilization, tell about the kind and function of objects and beings represented by means of geometrically defined schemes.

On the Egyptian murals, the most significant features were represented, both human beings and animals and plants. To create by illusory means spatial relations between them and their environment was an unnecessary matter. We even know that daily atmospheric events such as clouds, sunsets or blue heaven were not included on their paintings because they considered them forces contrary to human order. We have then that the primary theme of their representations was man: Human, civil and religious activities that Egyptians developed during the Pharaonic periods.

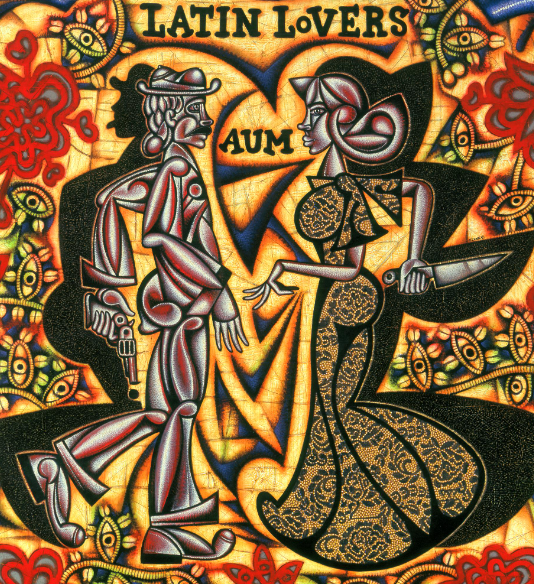

Let us put two and two together. The way in which Egyptians represented the human figure, such a singular method that R. Arnheim gives an autonomous validity in “The Egyptian Method”, consists of: masculine and feminine figures, standing or sitting, with heads and legs in profile but their torsos seen from the front, frontally. The eye of the individual who also “had” to show himself in profile is drawn frontally. We can recognize this same scheme on the paintings of Carlos Luna. Obviously, there does not exist a total transposition. On the paintings of Carlos Luna we also find personages seen from the front but who maintain the same synthetic scheme of identification and expression. But most of them are individuals in profile with eyes seen from the front. Such representation method reinforces the object’s direct impact, its identification without preambles.

The imagination that Carlos Luna has handled until now presents man as main theme, as ordering center of all events, of all circumstances. Of course, this has to do with an individual with a different context to the Egyptian one and therefore, with another story to tell. But before reviewing possible coincidences in the message, we should mention those representative ones.

The fact that Egyptian painting was a media for telling stories does not exclude the artistic refinement. The purity of the line and the fine harmonization in handling the color achieve impressive results. Luna has also demonstrated a great technical depuration, above all in his recent series where the chromatic range has extended and the line acquires form quality and vice versa.

He also shows an innovative discontinuous line, like “Embroidery”. This element plays a double roll: the one as embroidery as it is, represented as a part of the garments of his personages; and as illusory embroidery that fastens the personage as it was a big piece that have been cut on the fabric on which it is painted. Another striking and innovative element is the embroidery fabric representation with which he dresses his personages: meticulous filigree of matter and color. All these elements create a true “visual party” that catches inevitably the spectator’s glance.

The symbolic imagination also shows amazing coincidences. How many times Carlos Luna has shown us that personage with human body and rooster head, like the individual who acquires through the nahual the qualities of his brother animal; obviously, superhuman, semi-divine qualities. This personage is not far away from the representation of diverse Egyptian divinities that show human bodies and animal heads; personages like Horus, the falcon good, Anubis, the jackal good or Sebek, the crocodile good.

And that mysterious personage from whom we only see his half frontal face appearing; on occasions playful, on others sinister, and it is but an interpretation that Luna makes from Elegguá, the child saint of Yoruba cemetery. This personage also finds his equivalent in Aton, the solar disk, the only god imposed by Akhenaton, the heretical pharaoh. This representation appears on numerous murals and bas-reliefs in Tell-el-Amarna, solar disk that emanates its effluvium over Akhenaton and his wife Nefertiti.

The relations found do not mean in any way an appropriation. On the painting of Carlos Luna we equally find reminiscences of other representative styles but coincidentally primitives: Etruscan, Africans, Byzantines. This reveals that Luna’s painting has surged from the springs in a natural way. He maintains this filiation with the multicultural roots of his homeland, roots that are truly aged. We know well that this same heritage has given fabulous fruits in the work of other creators.

Evidently, Carlos Luna’s painting offers its own attributes: Exuberance close to stridence, technical refinement, vibrant coloring and a festive and popular humor but at the same time a refined humor. Besides, the Mexican context is making itself felt in his work, mainly in the chromatic and craft baroque style.

The guarantee that offers us to recognize valuable origins of his painting allows us to approach now (through the singular Egyptian parallelism) to the motivations, which generate his work, to that constituting real art, to his soul. And we can play then with the perspective that time and space give us.

We already saw that both the Egyptian murals and Luna’s painting tell us stories, stories centered in man and his context. In both cases, a similar representation method is handled, which reinforces the expression of both discourses. However, Egyptian stories show us a thematic diversity determined by daily events: work, social status and religion. The painter is limited to the impersonal chronicle. In other cases of primitive representation, as it is the Byzantine and Romanic painting, the thematic panorama is smaller because the painter was only committed to represent the Christian iconography: God-Christ, the Virgin and the Angelical Chorus. Obviously, by applying a schematized imagination.

Suchartistic autonomyachieved by the thematic delimitation, but above all by schematization and reiteration, creates a virtual barrier, a separation. The spectator becomes helpless witness of a different order to that traditionally human, an inaccessible dimension but at the same time a fascinating one.

The work of Carlos Luna has reached this point. Curiously, the barrier which we refer to takes shape in his paintings through a constant element in his work: the curtains, festive barrier that accentuates the presence of the personages and their peculiarity; but that also delimits us a scenographical space which we cannot penetrate but only admire.

His iconography, completely decodable, shapes concepts such as: cultural identity (Cuban personality), personal identity (virility) and irony. Irony certainly produces humor.

The artistic autonomy reached by Luna surpasses the quest for a style that has achieved, penetrating the primitive territory that seeks to capture the spectator’s attention, the imposition of his presence and to fill the possible emptiness with his work.

Fortunately, we are not in front of a product of the thousand-faces monster called mass mediaand neither before the work of an Egyptian chronicler-painter. We are not either before the dictator who imposes doctrines that are emptier each time, being it from the throne or from the pulpit. We are instead in front of a free artist’s work, but he is disciplined in a belief: the one of himself and of the limits he by himself is marking. His own serial development has demonstrated this.

For the moment, it is enough to let ourselves be bewitched by the Compay’s stories: a noisy and rich Guajiro who takes care of his banana plantation, who is able to feel nostalgia, who is able to feel the effect of fever and who, in his frenetic discourse, seems to be dancing like and Egyptian.

Back to WRITINGS

Back to WRITINGS